Any of you who know about aphids of North America (i.e. approximately zero in the ecological scale of things) will know that G.F. Knowlton is one of the leaders of the field in the early 20th century, leaving us with much good, and not so good, research and taxonomy. For many years I have hoped to visit his collection, housed at Utah State University. Thanks to a Toastmasters event that Gina needed to attend, we both visited Logan over the weekend of May 19-22, and I had the chance to look through Knowlton’s collection for about 6 hours. It was housed in slide boxes, similar to my collection, but the unidentified material was almost all lumped into 17 boxes without sorting to genus. I was interested to see that Knowlton collected mostly in towns and cities, and perhaps easily accessible countryside. I saw few slides from really challenging places such as we like to visit (see below).

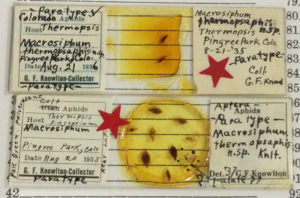

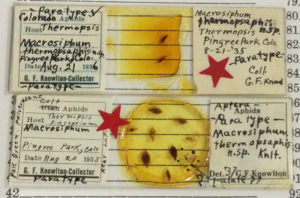

Some co-type material of a poorly known Macrosiphum aphid.

It was good to see the material from his earliest days (1920s), in which he wrote enthusiastic notes on the slide labels about biology, host plants, etc. Some of the slides in the collection are badly prepared in a way that is so bad it is hard to describe. Others are very nicely done. I managed to find almost a full box of Macrosiphum in the undetermined material, some of which were very interesting specimens.

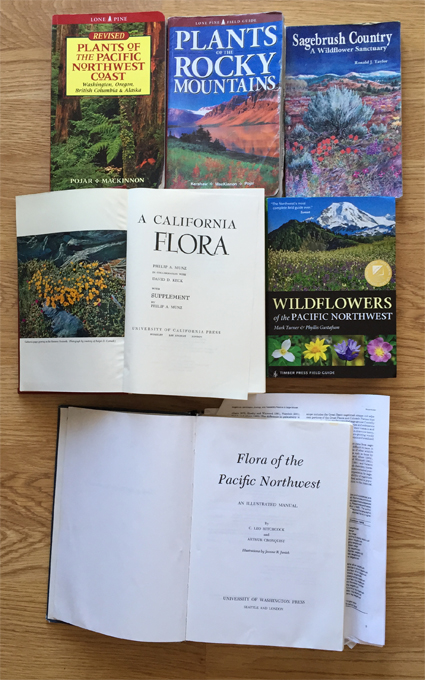

One of my goals of the trip was to collect in Knowlton’s old stomping grounds around Logan. With a couple hopefully rain-free afternoons looming, I set out for a couple hours into Logan Canyon. My overall impression is that the Canyon would be almost unrecognizable to the 1930-ish Knowlton from a botanical perspective. Other than the shrubs and trees, almost all the plants visible this time of year were invasive weeds, from a series of grasses dominating the roadsides and understory, to dyers woad (Isatis tinctoria), to things like burdock (Arctium) two meters tall, and entire wet openings filled with Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense). Although the landscape was very green and lush, a closer look betrayed the fact that the weeds were the greenest part, and the native plants struggled to show their heads in the shadows and forest understory. In places where I’d expect an understory of Indian paintbrush (Castilleja), Agastache (horse mint), Delphinium (larkspur), and various composites, I found grasses. Epic grasses. Grasses so big that the snowberry struggled to see the sun through grass litter laid down last season. The weeds were well into their season, but the native plants were just getting started, and the extremely few aphids I found betrayed this fact, e.g. just-mature fundatrices of Nasonovia (Capitosiphon) crenicorna on Geranium and Pleotrichophorus on Achillea. This was perhaps a place that inspired the rule we often see in the National Forests: “weed-free feed required beyond this point” except that the rule is way too late to have an impact in Logan Canyon (and the nearby Blacksmith Fork Canyon). The whole outing made me appreciate the Lakeview area, where even heavily used cattle pastures are waving fields of camas lily and other native plants this spring.

The final leg of the trip was a one-night-camp, destination TBD (to-be-determined) on the way home. Several hours of map-gazing and Google Earth-ing turned up no good ideas for the second half of the trip home, so off we struck, hoping for inspiration.

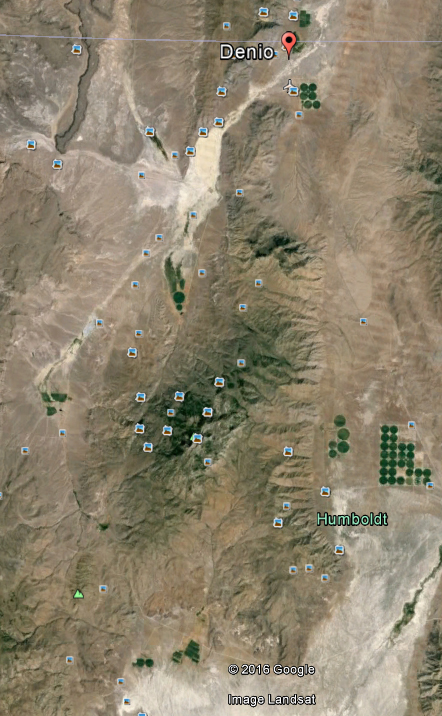

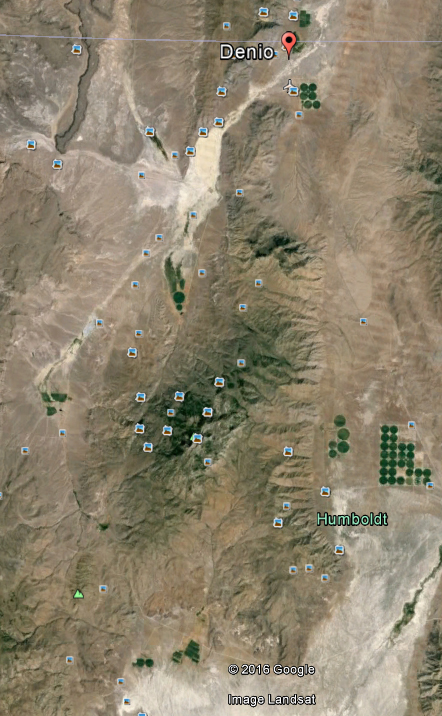

The Pine Forest Range from space, thanks to Google.

After a dud of an exploration of a terribly overgrazed canyon, where the stream was nothing but a matrix of cow footprints, with cow eyes watched us from behind every bush, somewhere between the 400- and 500- kilometer mark of the drive we saw a sign pointing into the Pine Forest Range of mountains in northern Nevada toward Onion Lake and Blue Lake (U.S. Bureau of Land Management territory). The road was wide and smooth and seemed not to go through any ranch homestead’s backyard (a common problem with roads in the remote parts of the western rangeland). We stopped in the paved highway for a few minutes to ponder (no traffic in sight for kilometers in either direction). In the end, “Why not!” Off we drove into the hinterland, the sign giving us confidence of good roads and sights to come. Bear in mind that the nearest town with an actual Main Street and things like a store and gasoline was Winnemucca, Nevada, about 109 km behind, or our home metropolis of Lakeview, Oregon, about 236 km ahead (we had recently passed a sign that said: “Next Gas 179 Miles” (that’s 288 km), that ‘town’ being Adel, Oregon that consists of a store-gas station-restaurant-tavern and precisely zero streets). We drove up a remarkably smooth dirt road for about 30 minutes to a potential camp spot, and waited for a bit to see of a rain shower would pass. Unfortunately, the mountain was creating the rain shower and it was not moving. So, up we climbed on the road. The landscape became more breath-taking with every moment, as did the lateness of the hour. About 90 minutes before sunset we picked a flat spot in a “saddle” at about 2200 meters elevation, and set up camp. By the time we had the tent set, the campfire going, and dinner almost done, the drinking water was starting to solidify and snow was threatening. But, the weather retreated, and we had a good sagebrush campfire ‘til late into the night.

Next morning the frost was thick and the drinking water partly frozen, but we were well-rested under the many kilograms of bedding atop the lovely air mattress in our tent. As with every camping morning, I got up early to make tea, coffee, and breakfast, then struck out for some aphid-hunting and botanizing. There were three different sage brushes in the area, at least two species of Ribes, at least one Symphoricarpos, two species of Tetradymia, an Amelanchier, and my favorite, nestled in the rock outcrops, Holodiscus ‘dumosus.’ The aphids were just getting started at this elevation, but I managed to find some presumed fundatrices of Pseudoepameibaphis, Pleotrichophorus, and Obtusicauda on the sagebrushes, plus some immature fundatrices of something green on Holodiscus. There was much potential in the area, but ideal collecting season is still at least a month away in a site like that.

Our camp spot down slope and the white bark pine forest far in the distance.

The drive home took us through the rest of the ‘road’ across the mountain range to the valley beyond (this is an area known as ‘basin-and-range’ wherein there are frequent narrow and steep-sided mountain ranges alternating with dry salty valleys). We passed along the edge of the Pine Forest, which is extremely unusual in being a forest of whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis). I really look forward to going back to explore the botany and insects in a whitebark pine forest at elevations of 3000 meters, one of the 5 or 6 whitebark pine areas in Nevada.