Myzus Passerini

This page updated: January 2025. Most recent updates: addition of taxonomic information on Myzus certus.

Myzus species are mostly introduced to North America from elsewhere. I have several species in my collection and all are introduced to North America, with the possible exception of Myzus cerasi, which is common in natural systems on native Prunus and Galium.

Species covered below (click on the name to jump to that species):

- Myzus cerasi (Fabricius)

- Myzus (Nectarosiphon) certus (Walker)

- Myzus (Nectarosiphon) linariae Holman

- Myzus (Nectarosiphon) persicae (Sulzer)

Myzus cerasi (Fabricius)

This is an apparently introduced species in North America, but is one of those that make me wonder whether it in fact has a natural Holarctic distribution.

Although it is best known as the cherry black fly, or cherry aphid, it is also a common find in native undisturbed habitats feeding on both native Prunus and native Galium (the secondary host). I have few photos of it partly because it has a propensity to be very active after its host material is collected and in a jar.

Myzus (Nectarosiphon) certus (Walker)

A valued colleague recently asked me look at some data on specimens of Myzus. He has samples from Caryophyllaceae that were reasonable to think might be M. certus. Some of his specimens seem to be intermediate in accepted identification keys. The available key characters to separate M. certus from M. persicae are given by Blackman and Eastop as follows (from the Silene key):

18. R IV+V in most specimens with only one pair of lateral accessory hairs (plus 0-3 ventral accessory hairs). Value of function CAUDA/(ANT III × PT) in range 0.80-1.52, but rarely more than 1.25 except in small specimens (those with ANT III less than 0.32 mm)…..Myzus persicae

– R IV+V in most specimens with two pairs of lateral accessory hairs. Value of function CAUDA/(ANT III × PT) in range 1.2-2.7 (rarely less than 1.25)…..Myzus certus

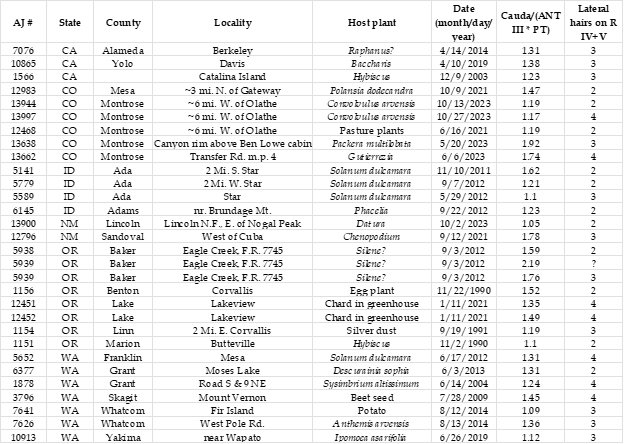

Because I’m generally skeptical about the utility of ratios of lengths in aphid species identification, I thought I’d lay out all my slides identified as M. persicae and calculate this discriminant and count R IV+V hairs on a bunch of them. Below is what I found.

A brief glance at these data shows that the discriminants used by Blackman and Eastop do not work for the North American samples I have gathered over the years. D. Hille Ris Lambers (1959) wrote that all morphs of M. certus are “red or reddish” and that in life M. persicae and M. certus are “extremely different.” This is what I recall from my two samples of M. certus, one from Dianthus in eastern Oregon (a very dry agricultural area) in March and another from Dianthus in western Oregon (a wet urban area) in November. These were dark colored in life, which is what prompted me to consider M. certus as the correct species identification back then (these specimens were identified in 1991 and 1992, before Blackman and Eastop’s biggest works). So, it may be that the only clues we have to recognize M. certus, at least in the parts of North America I frequent, is its host plants (usually Caryophyllaceae and sometimes Violaceae) and its brownish color in life. Below I present a photo of one of my slide-mounted specimens, which gives an indication of the dark pigmentation (but bear in mind that M. persicae can have dark appendages like this in cold conditions, see below).

Myzus (Nectarosiphon) linariae Holman

For a few years now, I have been aware of the presence in North America of another European invader, this species Myzus linariae that feeds on Dalmatian toadflax, Linaria dalmatica.

It was originally described from Central Europe where it was said to live on this plant in relatively warm and dry locations. For the past few years I have found it across the west in warm and dry locations where its host grows. So far, I know it from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Utah. Example localities include dry south facing slopes of the base of Mt. Timpanogos in Utah, on the shores of the Yakima River in central Washington, and along a highway in the high desert of eastern Oregon. It usually fits the key of Blackman and Eastop, easily separated from Myzus persicae by the longer tarsi and shorter processus terminalis.

In spring of 2015 I collected some of this species along the Salmon River near White Bird, Idaho.

At home, I transferred a few specimens to a bell pepper plant purchased from a major retail store. I allowed these specimens to either live or die on the pepper for several weeks. To my surprise, they eagerly reproduced on the pepper, producing what appeared to be normal apterae. After that first generation made up of entirely apterae, the second generation was partly alate — or at least it tried to be alate. Interestingly, all the alates that matured to adult on the pepper were horrifyingly deformed as in the specimens pictured below, with the wings variously developed into fluid-filled sacs rather than wings. What do you think about that?

Myzus (Nectarosiphon) persicae (Sulzer)

Although I have dealt with this aphid for almost 30 years, I confess little affection for it. My paid working life was in potato research management and I focused a bit on potato insect management. This aphid, commonly known as green peach aphid, is a major driver of pest management behavior by potato farmers in many parts of the world. I have collected and photographed this species many times in the course of my work. During winter of 2020-21, my small unheated garden greenhouse hosted overwintering Myzus persicae on perennial chard. Part way through winter the aphids had survived outside temperatures of about -5 C, so I opened the door and windows hoping this would allow the cold to reach and kill the aphids. As of February 23, aphids were still thriving on exposed young leaves despite brief periods of cold reaching -17 C. As I’ve seen with other aphids during winter, M. persicae become melanistic in these conditions. See photo below.

Now that we live in western Colorado (since 2021) I battle bindweed (Convolvulus arvenis) throughout our property. In one portion of our field, which used to be a cattle pasture, the bindweed grew especially lush and thick in 2023. In October I was walking past this patch and absent mindedly tapped on it to see what was living there, expecting the psyllid Bactericera maculipennis. Instead, I found unusually large, bright green (like a Granny Smith apple) aphids that were obviously Myzus. Upon slide mounting I had to call them Myzus persicae, but my goodness they looked unusual in life. I should have gotten a photo for all 3 of you who read these pages.