Macrosiphum Passerini

This page updated: February 2025.

Macrosiphum is my favorite aphid group, getting my start on its diversity and field biology way back in undergraduate years with exploration of the first host alternation of a fern-feeding species. In those days Sitobion was still used for some of the species now considered Macrosiphum; this brings up the point that the name Macrosiphum is now used for what is likely a polyphyletic assemblage of species. Some day it might turn out to be better thought of as 2, 3, or more genera.

Jensen, A.S., J.D. Lattin and G.L. Reed. 1993. Host plant alternation in two fern-feeding Sitobion Mordvilko. in: Critical Issues in Aphid Biology: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Aphids. P. Kindlmann and A.F.G. Dixon, eds. 142 pp.

Since then I finished a Ph.D. studying this group, and published 20 new species (so far, more to come). My impression of this group is that there has been recent and rapid diversification, especially so in western North America. There are many tightly host-specific species that are morphologically similar. But you should be able to see from the coverage of species here on AphidTrek that Macrosiphum species come in many beautiful colors and live in some fabulous ecosystems.

Jensen, A.S. 2022. A new species of Macrosiphum (Hemiptera: Aphididae) living on Silene (Caryophyllaceae). Zootaxa, 5183 (1): 75–89.

Jensen, A.S. and J. Rorabaugh. 2020. New Macrosiphum Passerini (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Information from Western North America Including One New Species and One New Synonymy. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 122: 81-103.

Jensen, A.S., R. Peña-Martinez, A.L. Muñoz-Viveros, and J. Rorabaugh. 2019. A New Species of Macrosiphum Passerini (Hemiptera: Aphididae) from Mexico on the Introduced Plant Pittosporum undulatum. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 121: 39-53.

Jensen, A.S. 2017. Two New Species of Macrosiphum Passerini (Hemiptera: Aphididae) from Dry Forests of Western United States. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 119: 580-600.

Jensen, A.S. 2015. Two New Species of Macrosiphum Passerini (Hemiptera: Aphididae) From Western North America. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 117: 481-494.

Jensen, A.S. 2012. Macrosiphum (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Update: One New Species, One Synonymy, and Life Cycle Notes. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 114: 205-216.

Jensen, A.S. and C.K. Chan. 2009. Macrosiphum living on Fumariaceae in northwestern North America, including one new species (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 111: 617‑626.

Jensen, A.S. and J. Holman. 2000. Macrosiphum on ferns: taxonomy, biology and evolution, including the description of three new species (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Systematic Entomology 25: 339-372.

Jensen, A.S. 2000. Eight new species of Macrosiphum Passerini from western North America, with notes on four other poorly known species (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 102: 427-472.

Species covered below (click on the name to jump to that species):

In January of 2025 I was considering what additions and amendments to do next on aphidtrek.org. At the time I had already covered 39 species in the page below and I thought it would be interesting to add all the other species in my collection, whether I have photos or not, to add some taxonomic comments here and there, and to think about what else might be useful or interesting to extract from my brain and put “on paper.” According Aphid Species File there are 162 valid, recognized species of Macrosiphum. Let’s see how many of those I have in my little personal collection (click on the name to jump to that species)!

- Macrosiphum adianti (Oestlund)

- Macrosiphum aetheocornum Smith & Knowlton

- Macrosiphum agrimoniellum (Cockerell)

- Macrosiphum albifrons Essig

- Macrosiphum badium Jensen

- Macrosiphum californicum (Clarke)

- Macrosiphum cholodkovskyi (Mordvilko)

- Macrosiphum claytoniae Jensen

- Macrosiphum clum Jensen

- Macrosiphum clydesmithi Robinson

- Macrosiphum corydalis (Oestlund)

- Macrosiphum creelii (Davis)

- Macrosiphum cyatheae (Holman)

- Macrosiphum daphnidis Börner

- Macrosiphum dewsler Jensen

- Macrosiphum dicentrae Jensen & Chan

- Macrosiphum diervillae Patch

- Macrosiphum dryopteridis (Holman)

- Macrosiphum equiseti (Holman)

- Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas)

- Macrosiphum euphorbiellum Theobald

- Macrosiphum funestum (Macchiati)

- Macrosiphum garyreed Jensen

- Macrosiphum gaurae (Williams)

- Macrosiphum gei (Koch)

- Macrosiphum ginajo Jensen

- Macrosiphum glawatz Jensen

- Macrosiphum hartigi Hille Ris Lambers

- Macrosiphum hellebori Theobald and Walton

- Macrosiphum holodisci Jensen

- Macrosiphum impatientis (Williams)

- Macrosiphum knautiae Holman

- Macrosiphum lambi Robinson

- Macrosiphum longirostratum Jensen & Holman

- Macrosiphum manitobense Robinson

- Macrosiphum melampyri Mordvilko

- Macrosiphum mentzeliae Wilson

- Macrosiphum mertensiae Gillette & Palmer

- Macrosiphum miho Jensen & Holman

- Macrosiphum niwanistum (Hottes)

- Macrosiphum occidentale (Essig)

- Macrosiphum olmsteadi Robinson

- Macrosiphum opportunisticum Jensen

- Macrosiphum oredonense Remaudière

- Macrosiphum oregonense Jensen

- Macrosiphum osmaroniae (Wilson)

- Macrosiphum pallens Hottes & Frison

- Macrosiphum pallidum Patch

- Macrosiphum parvifolii Richards

- Macrosiphum potentillae (Oestlund)

- Macrosiphum prenanthidis Börner

- Macrosiphum (Neocorylobium) pseudocoryli Patch

- Macrosiphum ptericolens Patch

- Macrosiphum pteridis (Wilson)

- Macrosiphum rebecae Jensen & Holman

- Macrosiphum rhamni (Clarke)

- Macrosiphum rosae (L.)

- Macrosiphum rudbeckiarum (Cockerell)

- Macrosiphum salviae Bartholomew

- Macrosiphum schimmelum Jensen

- Macrosiphum stanleyi (Wilson)

- Macrosiphum stellariae Theobald

- Macrosiphum tenuicauda Bartholomew

- Macrosiphum thermopsaphis Knowlton

- Macrosiphum tolmiea (Essig)

- Macrosiphum tonantzin Peña-Martinez, Muñoz-Viveros, & Jensen

- Macrosiphum tuberculaceps (Essig)

- Macrosiphum valerianae (Clarke)

- Macrosiphum vancouveriae Jensen

- Macrosiphum venaefuscae Davis

- Macrosiphum violae Jensen

- Macrosiphum walkeri Robinson

- Macrosiphum willamettense Jensen

- Macrosiphum wilsoni Jensen

- Macrosiphum woodsiae Robinson

- Macrosiphum zionense Knowlton

Well, that was fun! Seventy six of 162 species isn’t bad for a self-funded hobbyist’s collection. I thought I’d continue this listing process with a few comments on the North American ‘species’ I have not yet found. At the very bottom of this page I cover the forms I know of that are probably undescribed species. Click here to jump to that list.

Macrosiphum amelanchiericolens Patch

This name was created by Patch in 1919 for a form she found on Amelanchier spicata in Maine. Her description was based on one, possibly more, alate vivipara. About the only distinctive features she mentions in the very brief description is that the cauda is “comparatively short and rugged” and that the ANT III has “about 40 sensoria.” These facts suggest to me that she was indeed looking at something other than M. euphorbiae, but it is hard to guess what it might be. MacGillivray (1968) reported that Patch had discarded many of her slides that she thought worthless, including the type of this species. Therefore, we are left without an ability to recognize this species and nothing like it has apparently been collected on Amelanchier since 1914.

Macrosiphum audeni Macdougall

This form was described in 1926 based on material on the aquatic plant Nuphar polysepala (a.k.a., lily pad) from two sites in British Columbia, Canada. The description is wholly inadequate to recognize the species. I have searched Nuphar every chance I’ve had for decades without finding any aphids other than Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae. It may be a northern species, and it may require a canoe or a swimming suit to find. I made the following note to myself several years ago: “Extensive interaction with the CNC and Cho-Kai Chan (retired, of UBC, Vancouver) about the whereabouts of MacDougall types throughout 2008 and 2009 indicates that perhaps all her Macrosiphum types are lost.” This is a shame, if true.

Macrosiphum bisensoriatum Macdougall

Another poorly described species from 1926, this species is also not recognizable based on the description, and with the likely loss of MacDougall’s types, we may never know what this species is. I have collected avidly on all Ribes species for decades without finding any Macrosiphum specimens.

Macrosiphum (Neocorylobium) carpinicolens Patch

Here is a species, unlike the previous three, that is fairly well-known and moderately easy to find on its host Carpinus (hornbeam) in eastern North America. I was lucky enough to collect it several times while a postdoc at the U.S. national insect collection in Maryland. Alas, I did not grab any for my personal collection before leaving Maryland in 1999.

Macrosiphum constrictum Patch

This is a species I pondered quite a lot when in graduate school. It was collected on St Paul Island in the Bering Sea in 1913, using a species of Pedicularis as host. It has reduced reticulation on the siphunculi compared to many Macrosiphum, and is probably a good species. Alas, many years of collecting on Pedicularis everywhere I go has not turned up this aphid, and I have unfortunately never gotten the chance to go collecting in the Bering Sea.

Macrosiphum corallorhizae Cockerell

This is a name coined by Cockerell in 1903 for Macrosiphum aphids found feeding on the myco-heterotrophic orchid Corallorhiza maculata in New Mexico. As typical in those days, the description is inadequate for species recognition. I have seen two samples of Macrosiphum aphids on Corallorhiza over the years, and to me they look like large M. euphorbiae. Further, I think it highly unlikely that there would be a host-specific aphid on an ephemeral myco-heterotrophic plant. Finding thriving populations of M. euphorbiae on such a plant, however, would not surprise me at all.

Macrosiphum (Neocorylobium) coryli Davis

This species is known to feed on Corylus across much of northern North America. Despite collecting on Corylus anywhere I find it, I have never found this species. Like a few other species, I think I might have more luck finding it if I spent a good chunk of collecting time in Canada or across the U.S. near the Canadian border; I’ve noticed over the years that aphids and plants seem to recognize the international boundary, becoming noticeably different almost immediately after crossing the border.

Macrosiphum echinocysti Bartholomew

This form was described in 1932 based on a single very large sample collected on Echinocystis lobata (a.k.a., wild cucumber) in San Francisco, California. The description and figures are inadequate to recognize this form, and it has apparently not been collected since the description. When I visited the bay area in the 2000s I saw this plant growing in yards and along streets in the Berkeley area, and could not find any aphids. Bartholomew similarly noted that after that first collection he was unable to find this aphid in subsequent years. I suspect his form was an unusual host and appearance of M. euphorbiae.

Macrosiphum floridae (Ashmead)

This name was coined in 1882 for some aphids found in Florida feeding on Rosa. Apparently the types are either lost or were never designated, and the description is very poor by modern standards. Despite the intense insect monitoring characteristic of the Florida state government, no unusual rose-feeding Macrosiphum species has ever since been collected there. I suspect this aphid may have been a Wahlgreniella or perhaps a Rhodobium. Resolving the status of this name will probably require consultation of the dreaded International Code of Zoological Nomenclature to figure what can be done with what is probably a name without a species.

Macrosiphum fuscicornis Macdougall

From her description I am leaning toward this species being valid. The apparent loss of all Macdougall Macrosiphum types (see above) is of course not helpful. The fact it was recorded as a dark green color with relatively dark appendages would seem to rule out two common species, M. valerianae and M. euphorbiae. Macdougall mentions that alatae are uncommon, appearing in June and August, which is consistent with a heteroecious species. So, might there be a heteroecious species up in Canada that fits what Macdougall saw 100 years ago?

Macrosiphum geranii (Oestlund)

Despite many years of study and collecting I am still not sure what this name applies to. I see quite a diversity of Macrosiphum living on Geranium in North America. In my own collection I have samples sorted into 4 groups: those easily identified as M. aetheocornum, a group of specimens that look like M. euphorbiae that are trying to look just a little wrong, some that look like M. aetheocornum with relatively sparse setae, and a fourth with long thin siphunculi, a fat cauda, and abundant spinules ventrally on the head. I suspect that Oestlund’s species is not among these, but I am not sure I can recognize what he had if I see it. Many years ago when studying at the U.S. national aphid collection (USNM) I wrote, “The material in the USNM is obviously composed of two species. There are 25 slides of a species from Manitoba and Wisconsin that has a smooth venter of the head, but a very spinulose cornicle. This species also tends to have more setae on the URS. The other species is material from PA, MD, IL, and it has more normal looking cornicles, but densely spinulose ventral surface of head. This one also has URS with 6 accessory setae. One specimen from Manitoba appears to be M. euphorbiae, while the specimen from Sask. is a nymph.” So it seems likely that there are 2 to 4 species currently being confused under this name. The identity of this species might best be resolved by collecting on wild Geranium in and near Minneapolis, which is where Oestlund was working and collecting in the 1880s.

Macrosiphum hamiltoni Robinson

A.G. Robinson described this species from Humulus (cultivated hops) in 1968 (I was fortunate enough to learn much from Grant during our correspondence via paper letter and email during the 1990s). It is surprising to find a new Macrosiphum species living on a cultivated non-native crop plant. When studying material in the USNM I wrote, “I think Eastop is wrong in calling this species the same as the one on Cornus. This is closer to Illinoia than that Macrosiphum species, based on several paratypes and other material. No alates in the collection. The head is pale, the antennae with banded joints. Is this one related to M. olmsteadi?” So anyhow, I think this is a good species with a very mysterious biology deserving further study in the Winnipeg area (Manitoba, Canada).

Macrosiphum jasmini (Clarke)

The aphids Clarke based his description on were collected in Berkeley, California around 1902 living on Jasminum, a non-native ornamental plant. His description is very brief and inadequate. While visiting the University of California insect collection in Berkeley some years ago i wrote, “Types are probably lost. The slide at Berkeley labeled as type is obviously a mis-labeled sample from another collection in Clarke (1903); the specimens were Hyperomyzus. Hence, types must actually be lost.” During this trip I spent an afternoon walking all over Berkeley and the university campus looking for this and a few other species originally collected there. Although I did find some Jasminum, I found no aphids feeding on it. I suspect the aphids Clarke studied were M. euphorbiae.

Macrosiphum lilii (Monell)

This species has been collected in several states of eastern U.S. I had the chance to look at this material when studying at the USNM. I wrote about it, “This species has dark tips of femora, bases and apices of tibiae, and antennae usually dark, with middle part of III normally lighter. Based on many specimens from the eastern U.S. This is possibly an Asian species, and relationship to Japanese and Chinese species should be explored. May also be native to eastern North America?” While living in Maryland for 3 years I avidly searched for this species without success.

Macrosiphum orthocarpus Davidson

This form was found living on Castilleja exserta (recorded as Orthocarpus, owl clover) near Stanford University in California during the few years before 1909. This plant is a hemiparastic annual, so I strenuously doubt that an aphid would be monoecious on it. Davidson’s description is very brief. Considering these facts plus the commonness of M. euphorbiae on Castelleja, and my examination of the type material in the USNM (2 alate viviparae) I suspect that what Davidson had was M. euphorbiae.

Macrosiphum pechumani MacGillivray

This distinctive species lives on large lily-like plants such as Maianthemum racemosum in eastern North America. I was not able to find it in my handful of collecting trips in the region, but I have studied specimens in the USNM and it is clearly distinct and interesting.

Macrosiphum pyrifoliae Macdougall

Another of Macdougall’s species the types of which are apparently lost, this one was described from Sorbus sitchensis (then recorded as Pyrus occidentalis). Other specimens have apparently been collected near the type locality, and were said to be very similar to M. euphorbiae. Whether this is a good species cannot be known for sure at present. Further study in the field in British Columbia would probably help (despite decades of looking for aphids on Sorbus, I have never found a Macrosiphum).

Macrosiphum raysmithi Hille Ris Lambers

This species has, like several others in this list, received a lot of collecting effort over the past 3 decades, so far without luck. Originally collected on Lonicera involucrata var. ledebourii in Berkeley, California, it is distinctive among, but clearly part of, the group of Macrosiphum species that live on Caprifoliaceae around the Northern Hemisphere. During my trip to Berkeley in 2014 I explored every nook and cranny of the university campus looking for Lonicera shrubs that might host this species. I think I ended up finding a plant or two, but not this aphid.

Macrosiphum tiliae (Monell)

This is another story of a failed collecting expedition. I have been intrigued by this distinctive tree-feeding aphid for decades, and in 2017 we planned a trip to the Midwest (especially Wisconsin and Minnesota) in May to visit family and collect aphids. The key collecting targets of this trip were a few Macrosiphum species including M. tiliae. Alas, that particular year featured a late spring, so we were 2 or 3 weeks early to see spring generations of tree-feeding aphids and I was not able to find M. tiliae.

Macrosiphum timpanogos Knowlton

This name was coined by George Knowlton in 1942 based on a single sample of an unreported number of apterous viviparae collected on Mt. Timpanogos in Utah on 23 July 1940. The host plant was not known, but Knowlton wrote, “Host? (probably from a lupine of some kind).” He may have deduced this because the aphid is very similar to the common lupine-feeding aphid Macrosiphum albifrons. I saw the type slide in the USNM and wrote about it, “This appears to be another synonym of M. albifrons, or at least closely related. The type slide is two specimens that are badly over-cleared.” As noted far below, I have concluded that the species Macrosiphum thermopsaphis may be valid despite decades of it being treated as a synonym of Macrosiphum zionense, and in the same way it is possible that Knowlton’s material represents a separate lupine-feeding species. Probably the only way to learn more is extensive field work in the area of Mt. Timpanogos. I have collected typical-looking M. albifrons from that part of Utah, but have never seen anything that I would consider unusual or would fit what Knowlton wrote about M. timpanogos.

Macrosiphum (Neocorylobium) vandenboschi (Hille Ris Lambers)

This is another apparently distinctive Corylus-feeding species from California. Hille Ris Lambers described it based on 2 apterous viviparae collected in Tulare County, California on 13 July 1961. Despite 3 decades of collecting on Corylus everywhere I see it, I have not found this species. That said, I have not collected in California anywhere near enough to understand its aphid diversity.

Macrosiphum verbenae (Thomas)

This name was coined in 1878 for some aphids collected in Illinois on Verbena. Based on specimens I have seen and some collecting I have done on Verbena over the years, I am almost certain this is M. euphorbiae showing some environment-induced variation in color and general appearance, a common and easily documented phenomenon in M. euphorbiae.

OK! That was fun too! In summary, my view is that there are still 16 species I should try to find in the U.S.A. and Canada, and that 7 of the remaining names just listed are probably not valid species, being synonyms of M. euphorbiae, M. albifrons, or perhaps other genera in the case of M. floridae. Cleaning up these 7 names should perhaps be a priority if I ever get around to publishing a complete work on Macrosiphum of U.S.A. and Canada (there is no way I could cover North America as a whole without many years of access to and collecting in Mexico, the likelihood of which is approximately zero).

Macrosiphum adianti (Oestlund)

In the late 1990s I had the great honor to collaborate with the late Jaroslav Holman on a paper that covered the fern-feeding Macrosiphum of the world. He had material from Europe, Mexico, and the Caribbean, and I had material from the U.S.A. and Canada. This collaboration was carried out entirely via email and old-fashioned paper mail, sending specimens and slides through the mail. Jaroslav was generous and a great collaborator. Our paper was published in 2000, as shown in the list above. In it we covered the details about Macrosiphum adianti, including a clarification of what this species was. We wrote about it:

“Biology and distribution. Macrosiphum adianti is monoecious on Adiantum pedatum L., with apterous males. Reproduction continues throughout the summer, but adults that develop in midsummer can be as little as one mm long. The aphid is rather rare, infesting only a small percentage of A. pedatum plants in any given part of its range. It has so far been found in British Columbia, Oregon, California and Minnesota. There is extensive new material in the Oregon State University aphid collection. One parasitoid, Toxares deltiger (Haliday) (Braconidae: Aphidiinae) was reared from this species in Oregon.

Systematic position. Macrosiphum adianti can be recognized by its small size (usually about 2.0 mm), peculiar, short siphunculi with little or no reticulation (Fig. 3D) in apterous viviparae, low antennal tubercles (Fig. 3E,F), metatarsal II longer than u.r.s., and abdomen with patches or bands of pale sclerotization. It is so far the only species of Macrosiphum collected on A. pedatum in North America. The only other aphid known from this plant in North America is Papulaphis sleesmani. Macrosiphum adianti and P. sleesmani differ primarily in the tuberculate, apically placed rhinaria on antennal segments III and IV for which Papulaphis Robinson was named. Macrosiphum miho is a similar species; the differences between the two are discussed under M. miho.

Taxonomic notes. Oestlund (1886) described this species in the genus Siphonophora (= Macrosiphum) from Hennepin and Ramsey County, Minnesota, feeding on A. pedatum. This was the first species of fern-feeding Macrosiphum described from North America. Ever since its original description, there has been much confusion about the identity of this species. Oestlund’s description was short and, by modern standards, of little value in recognizing the species. Robinson (1966) reported that the types for this species could not be found in the Oestlund collection. He consequently based his concept of the species on material collected in Illinois on Aspidium. We borrowed the slides used by Robinson to construct his concept of the species, and found that the specimens disagreed with Oestlund’s description by possessing siphunculi and appendages that were much too long. Coincidentally we discovered a small yellowish Macrosiphum on A. pedatum in Oregon. Following a search in the University of Minnesota aphid collection (where the Oestlund collection is housed), P. Clausen found material of the same species, these collected by Oestlund on Vancouver Island, British Columbia in 1907. These specimens agree very well with the measurements provided by Oestlund (1886). Therefore, these specimens are here assigned to the name M. adianti. The material used by Robinson from Illinois is described below as a new species, M. miho sp.n. The location of the types of M. adianti is still unknown.”

Since that time I have collected this species once in Washington.

Macrosiphum aetheocornum Smith & Knowlton

For some years this species was a major collecting goal of mine. I collected on geraniums of all kinds for many years before finding this aphid for the first time in 2010 in New Mexico. Since then, I’ve found it many additional times, including fundatrices and sexuales, proving monoecy. I find it on what I call Geranium richardsonii, a plant that seems to have a wide variation in habitat preference and is irritatingly similar to G. viscosissimum where their ranges overlap.

In 2022 I published some information on this species as part of my work on M. ginajo. I wrote: “Biology and Distribution. Macrosiphum aetheocornum feeds on native Geranium species, the species recorded

by this author have been Geranium richardsonii Fisch & Trautv. and Geranium viscosissimum F. & M. Some collections listed above were recorded as Geranium due to the author’s limited plant taxonomy skills, but some of these were almost certainly species other than G. richardsonii and G. viscosissimum. In plants that are partially sticky–glandular, post–bloom, or that have the common intermediate pink flower color, the author struggles to confidently distinguish between the latter two species of Geranium, so not all species identifications can be relied upon.

“Macrosiphum aetheocornum has a full–season life cycle with sexuales in September. This differs from another common aphid that frequently occurs on the same host plants, Nasonovia (Capitosiphon) crenicorna Smith and Knowlton. The latter species has an abbreviated life cycle with sexuales in July and early August. The author has studied an unidentified species of Amphorophora that also has an abbreviated life cycle on especially glandular–sticky populations of G. viscosissimum; this aphid may be Amphorophora coloutensis Smith & Knowlton, which has a similarly abbreviated life cycle, but available identification keys and references are inadequate for species identification. These aphids with abbreviated life cycles often occupy stands of Geranium in dryer habitats that dry out and enter dormancy during summer. Macrosiphum aetheocornum, on the other hand, with its full–season life cycle occupies plant stands in habitats that support vegetative growth all summer and into autumn. Typical habitats

for M. aetheocornum are forested riparian zones and the understory of pine forests, but it can also be found on hot and dry slopes with spring–fed wet soils (such as the slopes above Lake Abert in Lake County, Oregon). The author has collected M. aetheocornum in Oregon, California, Montana, Idaho, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado. It almost certainly occurs in neighboring states such as Washington, Nevada, Arizona, and Wyoming.”

Macrosiphum agrimoniellum (Cockerell)

This species was described by T.D.A. Cockerell in 1903 while he was living in East Las Vegas, New Mexico. I’ve been through the Las Vegas area a few times, and am fascinated to think what it would have looked like 120 years ago (it is nothing like Las Vegas, Nevada, in case you were wondering) and what the heck an entomologist was doing in such a tiny town. A quick look at Wikipedia shows that he was there teaching at what was then called the New Mexico Normal School, now New Mexico Highlands University.

His description was based on a single sample collected in Beulah, New Mexico on 27 July 1902 by T.D.A. and W.P. Cockerell (his wife). Interestingly, a search on Google Maps turns up no towns or places called Beulah in New Mexico. A couple web pages mention that Beulah is now a ghost town and is in San Miguel County, the same county as Las Vegas. Cockerell’s description was based on one or more alatae viviparae. He wrote:

“Winged female (full of young) — Large, light apple green (orange-ferruginous mounted in balsam), without markings; eyes black; femora with basal two-thirds light green, distal third black, or sometimes less (about 90 μ); distal 90 μ of tibiae, and all of tarsi, black; nectaries suffused with blackish; antennae dusky, joint 3 black except the basal 30 μ; third antennal joint with very numerous (about 32) protuberant sensoria, about equally distributed on the proximal and distal halves; cauda tapering, with a blunt tip, sides with bristles set on little prominences; no capitate hairs anywhere.

Length of body about 3 mm, wings about 3 ½ mm; other measurements in μ: — Antennal joints: (1.) 120, (2.) 110, (3.) 1100, (4.) 900, (5.) 730, (6a) 160, (6b.) 1230. Cauda about 450; nectaries 1000, with imbricated surface; beak 700 to 750; anterior femur 1000; marginal cell with substigmatic portion 380, and poststigmatic portion 660.”

Cockerell’s work in New Mexico has always interested me, and some of his species have been most difficult to find and identify. Re-reading this description makes me like him even more — he uses microns for measurements and also refers to the two sections of the 6th antennal segment as 6a and 6b, both practices that I have used and been criticized for. I feel vindicated. That said, we must note that this description provides very little useful information in recognizing the species. Thank goodness for the relatively unusual host plant!

You’ll notice that he uses a couple old-fashioned terms for body parts: nectary = siphunculus = cornicle; beak = rostrum; bristles = setae = hairs.

The first time I found what I think is this species was in early October of 2012 in Grant County, New Mexico, in the Gila National Forest, Railroad Canyon. I recorded the host plant as Potentilla, but at the time I had never knowingly seen Agrimonia before, so it is possible that I misidentified the plant. I see that Agrimonia striata is common in the Gila National Forest, so who knows what I was looking at. Targeting Agrimonia on our 2014 New Mexico expedition, I was able to find 2 alatae in the Lincoln National Forest near nogal Peak on 28 September. My one sample from Potentilla gracilis was from the Uncompahgre National Forest in western Colorado in July of 2022, and I am almost 100% certain about my plant identification in this case. These two specimens fit M. agromoniellum quite well except the ultimate rostral segment looks a bit longer and perhaps the hairs on it are finer.

As I wrote in my essay about Macrosiphum euphorbiae, clues that this species is not M. euphorbiae include the extra rhinaria on antennal segment III in both apterae and alatae, the usual lack of lateral tubercles at the base of siphunculi, and the slightly longer and hairier ultimate rostral segment.

Macrosiphum albifrons Essig

This aphid is one of the largest in the world, and is actually familiar to many flower gardeners: it feeds on lupins (Lupinus) and is sometimes called the ‘lupin aphid.’ It is widespread in North America and has spread elsewhere as well with its cultivated lupin hosts.

In natural systems, M. albifrons seems to be able to feed on many species of Lupinus, however, some samples seem to differ morphologically from others. I have suspected that more than one species may be involved, but have not had the time, resources, etc. to study the situation in detail.

One similar species is Macrosiphum zionense (see below), which lives on a lupin-like legume called Thermopsis in the mountains of inland western North America. M. zionense is usually yellow or orange and has dark antennae, siphunculi, and legs. Another nominal species, Macrosiphum thermopsaphis, was described from Thermopsis in Colorado back in 1938 by G.F. Knowlton. It was never recovered after the original collections and was sunk as a synonym of M. zionense in 1997.

During spring of 2024 I studied my samples identified as M. albifrons and M. zionense that were collected on Thermopsis. A key reason for this was to ascertain whether the pale green specimens I had collected over the years on Thermopsis were in fact M. albifrons as I had guessed. I was finally prompted to do this analysis by two collections in 2023 in which I found typical M. zionense with yellow/orange color and dark appendages together with specimens of the size and coloration of M. albifrons. Both forms were extremely abundant on large patches of Thermopsis, one in the La Sal Mountains of eastern Utah, the other in far western Colorado on Uncompahgre Butte. These sites are actually visible one from the other, perhaps 25 miles apart by air. Anyhow, looking at these samples of pale specimens on Thermopsis, it was clear that the specimens did not fit either M. albifrons nor M. zionense. They had fewer rhinaria on antennal segment III than M. albifrons, but more than M. zionense. Also, the fourth antennal segment was about the same length as the third segment. In short, the pale specimens on Thermopsis were easily separated morphologically from both other species. So, I referred to Knowlton’s original description of M. thermopsaphis. Here is what he said: “Apterous vivipara.-Color light green with a dorsal covering of grayish pulverulence… Taxonomy.- Macrosiphum thermopsaphis differs from M. zionesis Knlt. [sic] in having pale cornicles, shorter hind tarsi, and more secondary sensoria; it differs from M. albifrons Essig in possessing fewer sensoria on antennal III of aptera, and in antennal IV being almost equal to or longer than III, rather than 0.14 to 0.3 mm. shorter.” It turns out that my samples fit Knowlton’s notes perfectly. I therefore have labeled these slides and noted them in my collection database as M. thermopsaphis. This action is of course not an official nomenclatural change — it is for entertainment here on AphidTrek. Interestingly, I have a sample collected in the La Sal Mountains site from Lupinus at the same time. These are typical M. albifrons in terms of rhinaria and antennal segments. One of course wonders whether ‘M. thermopsaphis‘ could be of hybrid origin, but until the unlikely event that someone studies the issue, I think it best to highlight this distinct form using Knowlton’s name.

Macrosiphum badium Jensen

I studied this species extensively during my Ph.D. research in Oregon, where it was common in the forests living on Smilacina (a.k.a. Maianthemum, false lily of the valley). The description was published in 2000 when I wrote, “This species is monoecious, holocyclic, feeding on Maianthemum racemosa, M. stellata and M. dilatatum (Liliaceae). Egg hatch occurs during March in Oregon’s Willamette Valley as the plants are unfolding. Reproduction continues until June, when the apterae present at the time mature, and enter what appears to be a reproductive diapause through the summer. These apterae settle either among the fruits, when present, or on the lower leaves. Reproduction begins again in September, usually on the lower or most yellow leaves. The apterae that survive the summer give birth to oviparae and males. Eggs are laid below the surface of the soil along the plant stem. Males have only been observed in nature twice, despite many sincere efforts. The first apterous male was collected on the outside of a cloth bag enclosing a plant that had several oviparae on it. In 1994, males were quite easy to find throughout my normal collecting areas in McDonald State Forest. Some plants had several males, both alate and apterous. This occurred even though populations of the aphid overall were not dramatically higher than other years.”

In 2000 this aphid was only known from Washington and Oregon, but I have since collected it in Idaho and Montana.

Macrosiphum californicum (Clarke)

This is the name used for Macrosiphum feeding on species of Salix (willow). Based on 30 years of collecting, it is clear to me that there are at least three species of Macrosiphum using Salix as host. Let’s get into the details I have about this situation.

First it’s important to establish what we know about the original material and description of the nominal species, M. californicum. W.T. Clarke coined the name and described this species in 1903 from what was apparently a single sample (single specimen?) collected at Newcastle, California (northeast of Sacramento) on an unknown date within the 18 months previous to publication of the paper. He wrote:

“Californica, n. sp. — Apterous viviparous female.

Length of body, 1.92 mm; width, .77 mm. Length of joints of antennae: III, .35mm; IV, .38 mm; V, .50 mm; VI, .19 mm; VII, 1.08 mm. General colour green. Joints of the antennae and the tarsi black. Rostrum reaching to second coxae, tip black. Nectaries yellow-green, reaching beyond tip of abdomen. Eyes pale.

Small colonies on tips of new growth of willow. No winged individuals present. Newcastle.”

At first glance this description might seem devoid of useful information, but Clarke actually chose some good features to highlight here: the color green, the pigmentation of antennal joints, the lengths of antennal segments, and the fact that specimens were in small colonies on tips of new growth. I’ll come back to these features in a bit.

Now that we have this basic original information, where to go from here? I know. Let’s look at all the relevant material in my collection: 137 slides representing well over 100 samples and over 200 specimens from 9 U.S. states and 3 Canadian provinces.

What a luxury it is to attempt taxonomic clarification with lots of material rather than the old-fashioned way of evaluating species based on one to a few specimens! As I sorted, consistent differences emerged that I had not seen before. First of all, it was very easy to sort most of the material into three quite consistent groups that most likely represent species. Let me summarize these three, then cover what we can conclude about whether any of these is likely to be M. californicum as seen by Clarke, then consider what should be done with the whole situation.

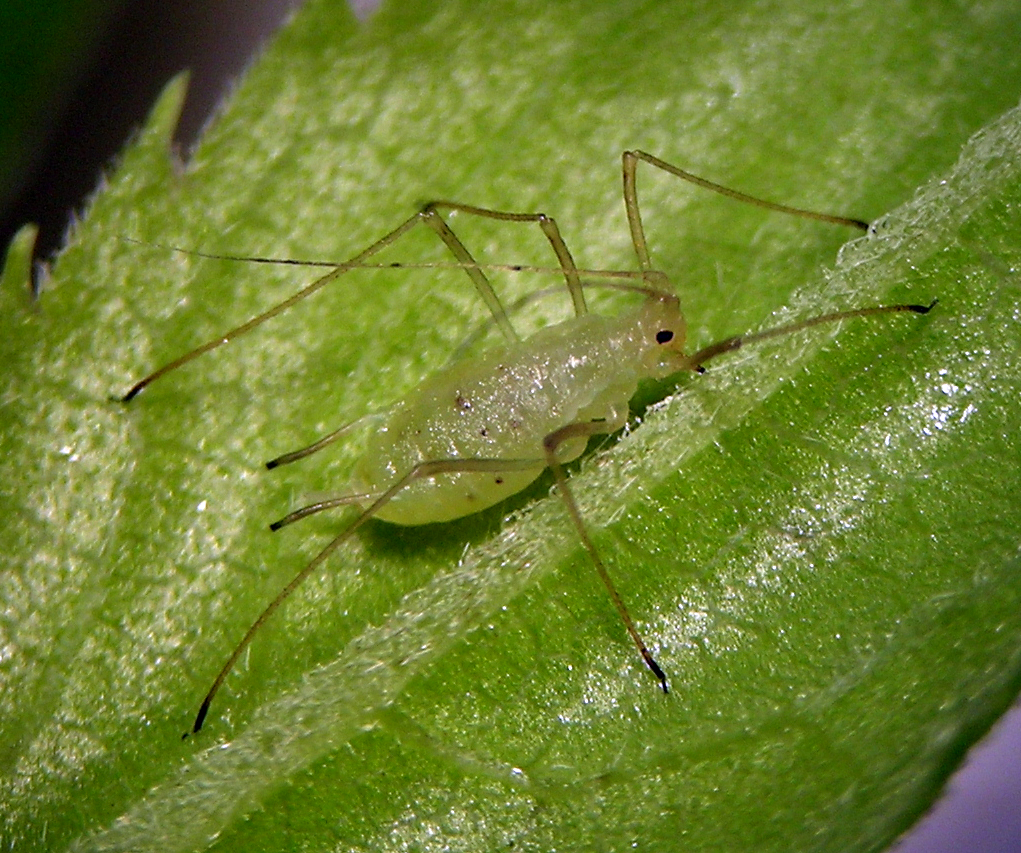

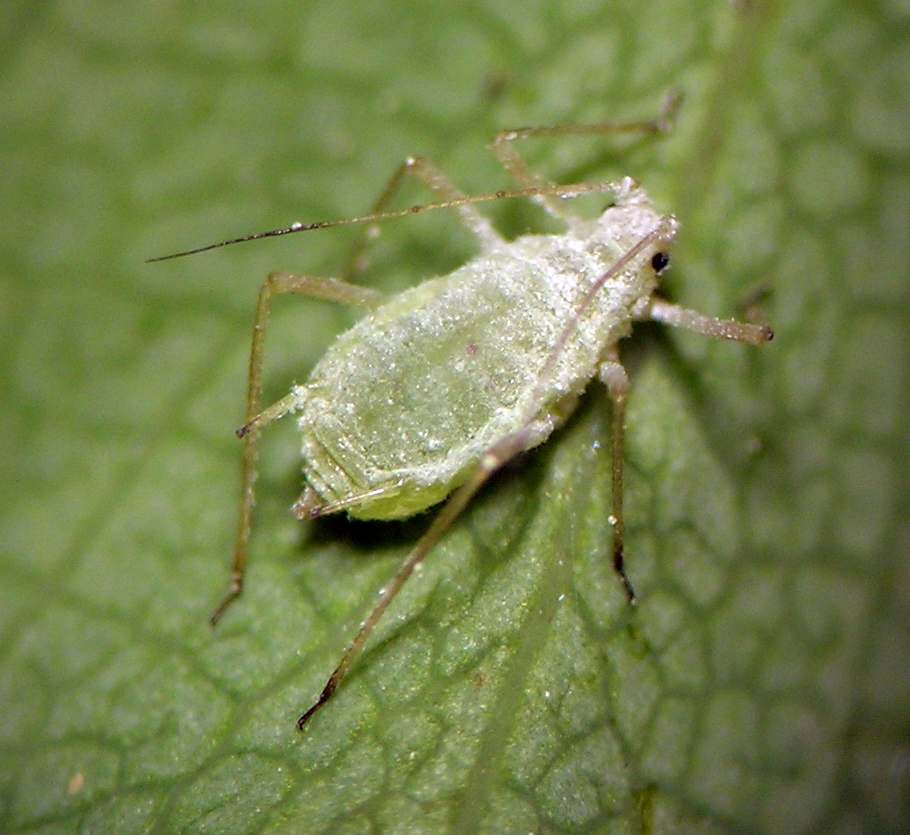

Macrosiphum ex Salix with ~5 pairs of cauda setae

This form is distinctive from the other two by having usually 5 pairs of lateral setae on the cauda; setae on antennae and middle parts of tibiae are longer, those on tibiae often trying to be fine and wavy; lateral and spinal tubercles are usually (always?) absent; ANT III is usually shorter than ANT V; ANT VIa (Base) is long, typically greater than 0.22 mm, up to about 0.34 mm; the R IV+V looks a bit broader and shorter, with about 6 accessory setae; the ventral surface of the head between clypeus and lateral margin has a distinct band of tiny spinules. In life the viviparae of this species are green or yellowish green with a dark green internal longitudinal stripe as in the photo below (this photo represents this form); the oviparae are orange with a darker orange internal longitudinal stripe, and my only note on alate male color is “yellow.” My samples of this form are all from the mountains in Oregon, Colorado, and Wyoming living in wet places on tall shrubby Salix species (alas I have zero knowledge in recognizing species of Salix). I have yet to collect an alate vivipara, these being rare in the sites I’ve gotten this form. Oviparae are abundant and easy to find.

Macrosiphum ex Salix with ~3 pairs of cauda setae and ANT VIa short

This form is the one I most commonly see in small to large colonies on growing tips of various Salix species and habitats from lowlands including the ocean coast to moderate elevation in the mountains. It is distinctive from the other two forms by having cauda elongate, nearly parallel-sided, with usually 3 pairs of lateral setae; ANT VIa not long, i.e., about 0.18 to 0.24 mm; antennae are often brown in alatae and dusky to brown in apterae, which have darker brown joints; ANT III is longer than ANT V; lateral and spinal tubercles are usually absent or very small on the abdomen; R IV+V has 4, sometimes 5 accessory setae; siphunculi in alatae are often brown beyond the basal fifth or so, sometimes brown in apterae as well; tibiae in alatae are often light brown and sometimes try to be brown in apterae. This is a very narrow-bodied form. In life it is green, usually without, but sometimes with a faint internal longitudinal darker green stripe. Interestingly, I have never seen sexuales nor fundatrix of this form. Does it host alternate? If so, I’m without ideas as to its primary host. I have material of this form from Washington, Oregon, California, and Idaho.

Macrosiphum ex Salix with ~3 pairs of cauda setae that also uses Cornus as host

For many years I’ve been collecting a large pale Macrosiphum on Cornus sericea (I’ve always called it Cornus stolonifera). This form was always evident in the spring, when it formed a generation of alatae, and again in the fall when I could find it re-colonizing Cornus and producing sexuales. One day about a decade ago I was collecting and realized that any time I found this form on Cornus there was Salix nearby and that in the late spring and summer the Salix often had a very similar aphid colonizing it. Aha! I thought. These may be the same species using both Cornus and Salix and that Cornus is apparently the primary host. Then for some years I lived in the high elevation dry forest habitat of south-central Oregon and had this plant-aphid system almost in my back yard. I was able to collect more samples from both plants that supported the host alternation, in terms of timing and morphological similarity, and I was able to do a couple reasonably conclusive host plant transfers from Cornus to Salix in spring.

This week’s evaluation of all my samples allowed me to further define the morphological features that unite all this material within and between the two host plants. These features are: cauda triangular, with pointy tip, usually with 3 pairs of lateral setae, sometimes 4; ANT III longer than ANT V; lateral tubercles usually prominent on abdominal segments 2-6; spinal tubercles usually present, sometimes quite broad and prominent on abdominal tergites VII and VIII and on the head; R IV+V usually with 6, sometimes 7 accessory setae; siphunculi are constricted apically with a slightly swollen portion basad. The alatae are usually light green or yellowish, the oviparae and alate males are white, or what I called “whitish green.” I have material of this form from British Columbia, Alberta, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado.

Miscellaneous samples

As is so often the case when sorting large numbers of samples from diverse locations and habitats, I have several samples that don’t match any of these three larger categories. A couple samples from Wyoming seem to be intermediate in appearance, a sort of blend of the forms I discuss above. One sample from New Brunswick, Canada is also a bit off, not quite fitting the other forms I sorted out. A few samples from coastal parts of Washington, Oregon, and California look different from all others. I remember collecting a sample from the Oregon coast on a Salix growing on the margins of the sandy beach. These specimens had a strange posture on the plant, being closely appressed to the leaf, with antennae laid flat forward of the head rather than swept back as is typical of many aphids. Based on this variability and extreme habitats that are Pacific Ocean beaches and coastal habitats, I suspect that at least one more species could be delimited with adequate collecting on the Pacific coast. The same might be possible through collecting along the east coast of North America, based on my single sample from New Brunswick. All of this of course ignores Mexico, which I know has a fair bit of Macrosiphum diversity.

What name(s) to use, then?

This mini-essay about M. californicum has been progressing from least nerdy to most nerdy topics. The most nerdy issue is, what name or names to use for these forms that seem to be 3 separate species? The name used over the past century has been Macrosiphum californicum (Clarke) because E.O. Essig suggested this some years after publishing the name Macrosiphum laevigatae Essig, 1911 and subsequently deciding that it should be a synonym of M. californicum. If Essig’s and Clarke’s names were referring to the same species, then the rule is that the older name take priority, i.e., M. californicum. A key question then becomes, are these two names referring to the same species? A second key question is, do these names seem to be appropriate for any of the three forms I discuss above?

Regarding the first of these questions, the short answer is that we will never know for sure because Clarke’s types (or perhaps better referred to as Clarke’s original material since I’m not sure he formally designated types) are lost and presumed destroyed in the massive fire that burned most of San Francisco in 1906. So, to determine whether the name M. californicum applies to Essig’s samples from his 1911 paper, must compare the descriptions. They both provide very little useful information. The most useful feature that they both mention is the length of antennal segments. Clarke’s numbers show that the ANT VIa was on the short side for these forms, i.e., 0.19 mm but that ANT V was substantially longer than ANT III. These two facts seem to not fit any of my forms since the one I have with ANT V longer than ANT III also has a long ANT VIa, nor do they fit M. laevigatae which had ANT V shorter than ANT III and ANT VIa with length about 0.22 mm in apterae. Clarke’s material came from inland California in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, while Essig’s material came from the California coast. So, based on this and evaluation of my samples, it is reasonable to think that these names applied to two different species. I found some cryptic notes I wrote at some point in the past that suggested I had seen Essig’s types of M. laevigatae but that I was unable to confidently link them to anything I had seen at that time (those notes are probably from 2010 or so). Bottom line answers to these two questions are: 1) It is not possible to tell based on the descriptions whether Essig and Clarke were looking at the same form; 2) I don’t think M. californicum clearly applies to any of the three forms I have sorted from my material. I suspect one or more of my coastal samples would be more likely as good specimens of Clarke’s M. californicum and there is no way to be sure what Essig was looking at without seeing his material again and possibly collecting fresh material from his locality (Santa Paula, California).

Conclusions

- I am 100% certain that more than one species has been lumped under the name M. californicum, and I think the true number is 4 or more species.

- One of these is almost certainly heteroecious between Cornus sericea and Salix.

- We cannot know what species Clarke was looking at based on his description, and Essig’s name is not much more useful without further study of specimens and fresh material.

- What to apply Clarke’s name to might require consulting the dreaded rules of zoological nomenclature in terms of what can be done with names that lack any attached specimens and have such scanty descriptions. For example, could we just pick one of my forms and assign the name M. californicum to it? Some people have done such things in the past, but I don’t know if such decisions conformed to the Rules.

- To resolve all these uncertainties and fully understand Macrosiphum on Salix in North America will require extensive collecting along both coasts and it wouldn’t hurt to do some exploring of Salix species in the interior lowland states and provinces.

- For now, it makes sense to discuss all this complexity under the name M. californicum.

Macrosiphum claytoniae Jensen

This is another of the 8 species I described in one paper that arose from my thesis research in 2000. Back then I wrote about it, “This species appears to be entirely anholocyclic. Hosts include Claytonia sibirica L. (Portulacaceae) and two other unidentified Claytonia spp. The former is the most important host. The aphid feeds throughout the year on its hosts, reproducing whenever temperatures allow. During the spring of 1992, normal apterae were found 29 February on a plant that had overwintered. Anholocycly was suspected at this time, but was not proven until the winter of 1993 when sexuales were not recovered from field colonies and did not develop in the laboratory. Also during this winter there was a 15 cm snow fall followed by temperatures as low -8°C. During the last day that snow lay on the forest floor, aphids were observed under the snow in cavities formed by overlying fern fronds. Temperatures at the time were about 2°C, and aphids were capable of sluggish movement when prodded.

This species’ biology is unusual not only because it is anholocyclic, but also because its most important host plant is not a perennial. In McDonald State Forest, Benton County, Oregon, most C. sibirica plants germinate from seeds in the fall and winter, often becoming very dense as they flower in spring and early summer. By late summer, most plants have died, leaving only a few very robust ones in drier sites, and a few plants of various sizes near streams. Thus each year this aphid species experiences a very severe population reduction as its plants die out. It often survives the dry season on plants near streams or seeps. It must remain on these surviving plants until mid winter, when the plants are getting larger, and preparing to flower. In some years, this species is abundant and widespread in McDonald State Forest in late winter and spring.”

Macrosiphum claytoniae is known only from British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon.

Macrosiphum cholodkovskyi (Mordvilko)

I have been collecting in Germany twice now, and found this aphid quite easily on Filipendula almost everywhere I looked. Good photos and other coverage of this species can be found at InfluentialPoints.com. This is a beautiful aphid, but lacks any special morphological features that jump out at me for recognition of specimens without host plant information. I have 5 samples on 9 slides from various places in Germany; these include apterous and alate females. I might share with you the original description and other historical information, but alas it is in Russian in a rather confusing 1909 paper (confusing for someone who does not read Russian).

Macrosiphum clum Jensen

A recently described new species, which I was alerted to by Blackman and Eastop’s books years ago. After many years of hunting on various Clematis species (none of which I could initially identify to species), I finally stumbled on this aphid using my standard beating tray technique of 30×30 cm plywood and paint stirring stick, tapping haphazardly on Clematis ligusticifolia.

Subsequently, I learned to find this aphid fairly reliably, and finally described it in 2015. In that paper I wrote, “This species lives in low densities on its host plant, mostly in exposed and dry or rocky sites. Numerous patches of C. ligusticifolia have been searched, and only a small percentage seem to host M. clum. Almost all collections of this aphid have been made by beating the plants over a wooden board. The aphids live so well-concealed on the leaves that the only time specimens were seen without beating was when they lived in some numbers on etiolated stems growing in the relative dark under a bridge near Weatherby, Oregon. Sites where M. clum was found were usually low elevation, near rivers in otherwise near-desert locations, and the plants were often rooted among boulders and growing up rock walls, along bridges, etc. In some cases I labeled slides with only the genus Clematis as host – this is simply due to my initial uncertainty about Clematis taxonomy. Clematis ligusticifolia is found from southern British Columbia and Alberta in the north to New Mexico in the south (Kershaw et al. 1998).” I still have specimens from only Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Macrosiphum clydesmithi Robinson

This is one of my most familiar species of Macrosiphum, and one of 4 that feed on bracken fern, Pteridium aquilinum. When in grad school in the early 1990s I worked out the taxonomy of all 4 species, including some mix-ups that had occurred in previous literature regarding identities of various fern-feeding Macrosiphum.

I published the results with a distinguished co-author, Jaroslav Holman, in 2000.

Back then I wrote about this species’ biology: “Robinson (1980) described M. clydesmithi from material collected in Utah and Oregon on bracken fern, Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. At that time its life history was not known. Jensen et al. (1993) reported the heteroecious life cycle of this aphid, demonstrating that its primary hosts are species of Holodiscus (Rosaceae). It was found on Holodiscus discolor (Pursh) Maxim. in the lower elevations and higher latitudes of Oregon, and on Holodiscus dumosus (Hook.) Heller in the mountains and more southern parts of its range in Oregon. Holodiscus discolor is also the primary host of M. pteridis (see below, under that species). In areas of western Oregon where the two aphids both live, their phenologies differ markedly from one another in the autumn.

Macrosiphum pteridis remigrates to Holodiscus a few weeks earlier than does M. clydesmithi, which may not arrive on Holodiscus until most of its leaves have fallen in October. Mating then occurs in M. clydesmithi on the last remaining leaves in November. On Pteridium, M. clydesmithi is most often found in exposed sites such as open fields and roadsides. It is not tended by ants despite the fact that it sometimes co-occurs with M. rhamni, which is often ant-tended. … Macrosiphum clydesmithi has an extensive known range in western North America, including Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Idaho, Oregon, Washington and southern Mexico.” In those days I studied this species on Holodiscus discolor ssp. discolor, which is a tall, upright shrub in and on the edge of coniferous forests. Since then I have found that this aphid is one of the common species feeding on Holodiscus discolor ssp. dumosus in rocky outcrops on the edges of mountains and cliffs at moderate to very high elevations.

I now have material of this species from Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Macrosiphum corydalis (Oestlund)

This species could have been added to this page a long time ago because I actually do have some nice photos of it. I must have forgotten that my valued colleague Cho-Kai Chan had sent them to me. He and I published a paper in 2009 that described a new species, Macrosiphum dicentrae, and covered what we knew about this one, M. corydalis. As I wrote in my essay about M. euphorbiae, this species looks much like a small version of M. euphorbiae. Key differences, as you’ll see in the photos below, are that it is monoecious on various Fumariaceae and has apterous males. An implication of these facts is that specimens are hard to identify confidently if we are not sure about the life cycle type and have no males.

I have material of this species from British Columbia (collected by Cho-Kai for our joint paper), Oregon, Wisconsin, and Maine. My Oregon samples were from disturbed sites on forest edges, while my collections in Maine and Wisconsin were on the tops of rock outcrops where the host plant Capnoides grew in cracks in the rock.

We closed our paper in 2009 with the following: “The types and other specimens from Minnesota are different from the west coast specimens in that the HT II is noticeably longer in Minnesota. While at first glance this difference stands out, the lack of other differences, the otherwise overall similarity in appearance, and the common host plants between Minnesota and the west coast have led us to use the name M. corydalis for specimens from both regions. It is of course possible that there are two species involved, but determining this with certainty will require much more work including collecting fresh material in Minnesota.”

Macrosiphum creelii Davis

This species is one of many that are very similar morphologically to M. euphorbiae, but that have distinct biology and ecology. M. creelii specializes on legumes, particularly Vicia and Lathyrus. It is often bigger than a typical M. euphorbiae, but not always. During many years of pursuit, I eventually gathered material of all morphs from fundatrix to sexuales. One of my favorite habitats to collect this species are the famous public beaches of Oregon. Just at the edge of high-tide water line there often grows a large Vicia, and on that there is almost always the largest and most dramatic specimens of M. creelii. In our local southern Oregon Ponderosa pine forests, M. creelii was uncommon but widespread on native Vicia and Lathyrus growing in the shade of conifers. In the forests of Utah and Colorado this species is often on legumes in aspen groves.

I’ve enjoyed digging up the old descriptions of some of these species, so let’s have a look at Davis’ description of M. creelii. Remember the 4 line description of M. californicum by Clarke, shown above? Davis’ work was the opposite end of the spectrum, covering 7 pages in his 1914 description of this species, including 3 plates of very nice drawings, text discussing its life cycle and potential as a pest, and detailed data on antennal segment measurements for many individual specimens. At the time this aphid was known as a pest of alfalfa in Nevada and Utah. You might be mildly interested in my very first published paper, in which I discuss this species: Jensen, A.S. 1992. Exotic aphids in Oregon. The Northwest Environmental Journal. 8: 217-218. In it, I suggested that M. creelii may have been displaced as a pest of alfalfa by the invasion of pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris). I have only seen one sample of M. creelii from alfalfa, and that was from an alfalfa seed field near Warden, Washington many years ago.

As with other aphid taxa, both species and genera, that seem to be specific to unusual host plants and that have more or less uniform appearance and morphology, we run the risk of lumping more than one species under a single name (see my coverage of M. californicum above). I suspect this may the case with M. creelii. We can easily slap the name M. creelii on all Macrosiphum specimens collected on Vicia and Lathyrus anywhere in North America as long as they look vaguely similar to each other and to their presumed close relative, M. euphorbiae. For example, in the dry aspen groves of the Southwest (i.e., Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona) we find a small legume, which I think is a Lathyrus, that often forms the main herb understory layer. Macrosiphum aphids are often common in these settings, and I file them with M. creelii, but they are very pale colored, relatively small, and give very different vibe to the more typical M. creelii found in the wetter forests and beaches of the Northwest. Are there two or more species represented here? I don’t know. It’ll take some creative work to figure that out.

I have collected this ‘species’ in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, Maine, and British Columbia.

Macrosiphum cyatheae (Holman)

This is a fern-feeding species first described from Cuba but subsequently collected on the mainland as well, in Venezuela, Costa Rica, and Mexico. Jaroslav Holman and I covered this species in our joint 2000 paper, and he kindly gave me some paratypes and one other sample from Cuba collected in 1965 and 1967. I recently remounted them from the water-soluble gum-based mountant into Canada balsam. The resulting specimens are actually quite good! In our paper we wrote: “Biology and distribution. This species was described from Cuba feeding on Cyathea balanocarpa DC. (Holman, 1974). It has also been found on Pteridium caudatum (L.) Maxon, and in Venezuela (Robinson, 1980). Most recently it was found on Pteridium and unidentified epiphytic ferns in eastern Mexico (Veracruz). All samples of this species were collected in the mountain cloud forest zone. Its life cycle is unknown. Holotype in the Institute of Zoology, Cuban Academy of Sciences, Havana. Paratypes in the BMNH, Institute of Zoology, Saint Petersburg, Russia and in the second author’s collection.

Systematic position. The siphunculi of this species often completely lack reticulation, and are remarkably smooth, explaining why the species has been placed in Acyrthosiphon. This lack of reticulation separates this species from nearly all other Macrosiphum. Also quite distinctive are its dark legs and antennae in both apterous and alate viviparae. Probably the most closely related species is M. clydesmithi, which also feeds on Pteridium, has reduced reticulation on the siphunculi and occurs far south into Mexico. Separation of the two species is easy using the characters just mentioned.”

Macrosiphum daphnidis Börner

I have collected this species only once, during a collaboration trip to visit Cho-Kai Chan in Vancouver, British Columbia back in 1993 while I was in graduate school in Oregon. He had discovered many adventive aphid species from Europe and Asia on the University of British Columbia campus, including M. daphnidis. This species is covered very nicely at InfluentialPoints.com.

Macrosiphum dewsler Jensen

This is one of my two new species described in 2017.

It is yet another example of a species I’ve known about for a long time, but spent 12 years gathering adequate information and specimens to support a good description. It is named after one of our deceased dogs, Dewey (also known as Dewsler, Mr. Dewsler, and Dewsldoerfer).

I wrote about this species: “This aphid

is monoecious holocyclic on its host Linum lewisii. As noted by Munz (1973), this plant occurs on dry slopes and ridges, mostly above 1,220 meters elevation in montane coniferous forests and pinyon-juniper woodlands. Personal observation makes it clear that this plant

begins its growing season early in the spring, and is highly drought tolerant through the summer and fall. The overwintering stage of the plant consists of

small above-ground shoots ready to grow immediately when conditions allow. The earliest collection I have made of M. dewsler was 3 June 2016 south of La Pine, Oregon. At this location, early June is very early spring in terms of plant growth, yet L. lewisii was in bloom and the aphid population thriving. I have not collected confirmed fundatrices of this aphid, the only possible specimens being these on 3 June 2016. I considered these specimens to most likely not be fundatrices, which means that egg hatch and population establishment must have happened remarkably early at this location. Aphid populations persist on the plant stems after petal fall and during fruiting, seemingly able to reproduce throughout the dry summer months. Alate viviparae are rare, possibly produced only during certain stages of the season or of plant growth, considering that my only alate specimens are from early in the growing season (early July in the mountains of northern New Mexico and early June in the mountains of southern Oregon). In life, this aphid is difficult to see on Linum plant stems, as individuals feed cryptically among the leaves.

Linum lewisii is naturally distributed throughout most of western North America (Munz 1973), and is closely related to the European Linum perenne L. (McDill et al. 2009). Although I have collected this aphid from only New Mexico, Oregon, and North Dakota (a sample from the latter state was secured while this manuscript was in review), it likely occurs where L. lewisii is found in similar habitats in Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, Idaho, and Washington. McDill et al. (2009) analyzed the phylogeny of Linum and Linaceae, and found that L. lewisii is closely related to Linum species occurring in eastern Asia. Considering this and their estimated time of diversification of L. lewisii from its Eurasian relatives (3.8-3.3 million years ago), they thought it likely the ancestor of L. lewisii colonized North America via the Bering Land Bridge. It would therefore be interesting to study relatives of L. lewisii in eastern Siberia to determine whether they may serve as host to M. dewsler or a close relative.”

Since the paper was published I have collected confirmed fundatrices in the forests of southern Oregon on 8 May 2020. I now have material of this species from Oregon, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, and North Dakota. It almost certainly lives in neighboring states as well.

Macrosiphum dicentrae Jensen and Chan

This is the species mentioned above from the paper Cho-Kai Chan and I published in 2009. He had studied it for a few years in the 1980s before i found it in Oregon in the early 1990s. Back then we wrote about it: “Biology and distribution,- This species is monoecious holocyclic, feeding on Fumariaceae, mostly Dicentra formosa (Andr.) Walp., but also found on Dicentra sp. (UCB), Corydalis scouleri Hook. (WSU and ASJ), and Corydalis aurea Willd. (collected by the second author). Based on the known hosts, it is likely to be able to feed on other Dicentra and Corydalis species. A detailed description of the life cycle for populations in Benton County, Oregon on Dicentra formosa follows. Both authors, however, have found populations producing oviparae and males as early as July. These specimens in every way fit the description given above.

In the Corvallis Oregon area, egg hatch occurs in mid-to late February, and fundatrices mature by the end of March, feeding on the young, unfolding leaves. The second generation is apterous and matures in April. The third generation is composed mostly of alatae and matures in May. Individuals in these two generations are most dense on the flowers and fruits, but can be found on the lower surface of the leaves as well. In McDonald State Forest, most of the alatae maturing in a given location remain in the patch of host plants in which they were born, mature specimens usually remaining on the leaves. Apterae reproduce very slowly throughout the summer until leaf senescence begins in autumn, when a fall spurt of reproduction occurs. Nymphal oviparae and males were present in late September, 1992. Male nymphs are a steel bluish color, and nymphal oviparae are white. Sexuales feed primarily on the leaves, mature throughout October, and by early November all males are gone. Eggs have never been seen during observations in Oregon, but the second author has observed eggs laid on the leaves in British Columbia.

This aphid is rare in the Willamette Valley of Oregon. The reason for this may be that few patches of its host remain green until autumn, and it is only these patches that are utilized by this species. It seemed to be more easily found in Washington along Puget Sound and in British Columbia in and near Vancouver. These areas are wetter throughout the year than the Willamette Valley, which may be the factor that allows more Dicentra formosa plants to remain vegetative during the summer. The populations that produced sexuales in July and August, mentioned above, may be in the process of adapting to drier locations in which the host plants die back during the summer.

When disturbed, all morphs of this species are apt to drop from the plant.

This species is known from western British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California.”

We went further to say: “The chief characteristic that separates this species from M. corydalis, M. euphorbiae and more closely related species like Macrosiphum tolmiea Essig and Macrosiphum violae Jensen is the fact that setae on the antennae and dorsum of the body are finely pointed (Fig. 9, 10), even in carefully prepared specimens mounted in gum mountants.” The final statement there about mountant type is relevant because if clearing for mounting can be done without the use of a caustic agent like NaOH of KOH (e.g., clearing using chloral hydrate solutions) most Macrosiphum species are revealed to have expanded glandular tips to their dorsal setae, making the setae look slightly capitate.

Macrosiphum diervillae Patch

This is one of the several species of Macrosiphum associated with Caprifoliaceae that I think are a closely related lineage. Other members of this group include M. stanleyi, M. schimmelum, and M. oredonense, among a few others including one undescribed species from southern Oregon. I made M. diervillae a collection target during our 2015 trip to northeastern U.S.A. and was able to find it 4 times in Maine and New Hampshire on its known host, Diervilla lonicera.

Macrosiphum dryopteridis (Holman)

This is another fern-feeder that Jaroslav Holman and I covered in our 2000 paper. I think of it as the European version of the North American species Macrosiphum walkeri. Both species feed on a wide range of fern species, and they look very similar as well. In our paper we wrote: “Biology and distribution. This species was the first fern-feeding Macrosiphum to be described from Europe. Holman (1959) reported finding it on Dryopteris dilatata (Hoffm.) A. Gray (= austriaca), Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott and Athyrium filix-femina (L.) Roth, in the mountainous parts of eastern and southern Bohemia, Czech Republic. It has since been found on Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Slosson in the Czech Republic and on Athyrium distentifolium Tausch in the Kola Peninsula, Russia. It is monoecious holocyclic with alate males, producing sexuales in September and October in the Czech Republic (Holman, 1959).

This species has been recorded from the Czech Republic, Germany, Finland, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden and the European part of Russia (Heie, 1994; Holman collections). All five hosts from which it is known are circumboreal in distribution (Hitchcock & Cronquist, 1973), so little about the aphid’s distribution can be deduced from the host plants. Types are in the collection of the second author, BMNH and some other places.

Systematic position. Macrosiphum dryopteridis is remarkably similar to the North American species M. walkeri. The only characters known to separate them are the normal presence of eight or more caudal setae in apterous and alate viviparae of M. dryopteridis as opposed to M. walkeri which most commonly has seven setae. It is possible that they are synonymous, but a conclusion in that regard must await examination of material from throughout the full ranges of both species. This should include collecting on ferns across Russia and through Alaska south to Washington. Macrosiphum dryopteridis is also similar in many respects to M. miho, as discussed under that species.”

I have two slides from a single sample collected by Holman in Czechoslovakia in 1986. In 2008 I remounted the specimens from a gum mountant into Canada balsam.

Macrosiphum equiseti (Holman)

Embarrassingly, I was thinking that this was a species that Jaroslav Holman and I covered in our fern Macrosiphum paper of 2000. It feeds on Equisetum (horsetails), which are obviously not ferns, but I thought we’d covered it. Looking at the paper, it turns out we did not! Anyhow, it was described by Holman in 1961 from Equisetum silvaticum and Equisetum pratense collected in Czechoslovakia during 1960. This is another species that Cho-Kai Chan discovered in Vancouver, British Columbia. Many years ago I studied some of his specimens and compared them to Holman’s material. They are very similar, but I have to admit wondering whether the North American and European forms might be separate species, in a similar fashion to M. dryopteridis and M. walkeri on ferns in Europe and North America, respectively. Over the past 30 years I have tapped on scores of patches of Equisetum in all sorts habitat types from urban settings like Cho-Kai collected in, to mountain slopes, stream sides, and forest fire burn scars. I have found it twice: once in July of 2012 in the Uintah Mountains of Utah on a slope that was recovering from a fire about 10 years previous. The second time I found it was in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest in eastern Oregon, living on streamside Equisetum in a very shady site. This work implies that it is widespread but uncommon. My other specimens are all from Vancouver when I was collecting there with Cho-Kai in 1993.

Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas)

In May of 2021 I was scrolling through this collection of blurbs about species of Macrosiphum when I noticed that I’d never posted information about the most widespread and well known species of this genus! It’s time to correct that oversight.

Often known as potato aphid, Macrosiphum euphorbiae is native to North America and has spread throughout most of the world. It is one of the most polyphagous aphids known, with many hundreds of documented hosts, and almost certainly there are many hundreds of additional plants that would be acceptable hosts if this aphid were given the chance.

The basic host plant biology in temperate climates is heteroecious, with overwintering on Rosa followed by migration to its many summer hosts, which can be trees, shrubs, and herbs (both monocots and dicots). Many aphid collectors (including myself) have found oviparae and eggs of this aphid on herbaceous hosts, but whether and to what extent it can successfully overwinter on plants other than Rosa is not known. Indoors or in warm climates this aphid can be anholocyclic.

My sense is that M. euphorbiae is likely native across most of North America, but in my experience its prevalence and diversity of appearance and habits is most extreme in the northwestern U.S. states and western Canadian provinces. In these regions there are times when most aphids found in natural systems, such as forests and meadows, are M. euphorbiae on its many secondary hosts. This can render any search for less common aphids a frustrating affair because M. euphorbiae seems to displace many other species.

As a pest of potato in the northwestern states where my experience is greatest, this aphid is an early colonizer, arriving on potato in places like eastern Oregon and Washington shortly after crop emergence (e.g. mid-late May to early June). It rarely stays in the crop beyond July 1, after which green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) takes over. Its ubiquity in natural systems across much of northern U.S.A., however, means that most potato crops are growing near native populations of potato aphid that could pose a threat, especially as virus vectors.

Taxonomically M. euphorbiae is challenging due to its lack of unusual features and because of its extreme variability in both color and morphology. A practical consideration for a taxonomist like myself is whether Macrosiphum specimens found on an unusual plant are typical M. euphorbiae, or M. euphorbiae that look different due to stresses imposed by climate, host plant, or microhabitat, or whether the specimens belong to a separate species. There are now many well-understood species of Macrosiphum around the world that look remarkably similar to M. euphorbiae but that have distinctive biology and life cycle with very slight morphological differences.

Below I present a range of photos of this species, showing all its morphs and some of the range of variation in appearance.

Macrosiphum euphorbiellum Theobald

This species has been reported from one location in North America and I’m afraid I’m the guilty party. On 26 February 2015 I collected some unusual-looking Macrosiphum from an ornamental Euphorbia growing in the landscaping of Washington State University’s Mount Vernon research and extension center. This site is near the Pacific Coast, so late February is early spring there and many plants are actively growing. It is also a place with warm-ish winters that allow many plants to remain green throughout. My sample included both apterous and alate viviparae. These specimens immediately struck me as something other than M. euphorbiae because of the pigmentation of the legs and siphunculi, the short broad R IV+V, and the long-ish ANT VIa (Base). Using the key to aphids on Euphorbia provided by Blackman and Eastop, they run fairly smoothly to M. euphorbiellum except that the R IV+V appears to be a bit too short compared to the ANT VIa. Nonetheless, I still conclude that my identification is probably correct based on other features and the nice summary of the species provided by InfluentialPoints.com. If I end up deciding I was wrong, I will try to clarify that here.

Macrosiphum funestum (Macchiati)

Another species I have collected several times in Europe, this one feeds on Rubus, especially blackberry (e.g., R. fruticosus). The first time I collected it was in 1993 during my stay in Czechia for the one and only international aphid symposium I have attended (thanks to my co-major professors Gary Reed and Jack Lattin for the financial support of this trip). The aphid lived on the campus of the university where we stayed. It was quite an experience going to Czechia just a few years after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia. I was extremely uncomfortable in social situations (I often still am), and in a milieu where most people spoke languages other than English and were from unfamiliar cultures, I was a fish out of water. I also collected this species several times during our 2 trips to Europe in the 2010s. As is so often the case with European aphid species, InfluentialPoints.com has a nice page on this species.

Macrosiphum garyreed Jensen

This is the second new species I published in 2017. It is named after my undergraduate and graduate supervisor and mentor, Gary Reed.