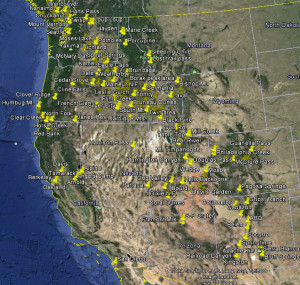

Our first full weekend outing of 2016 was to Juniper Mountain in Lake County, Oregon the first weekend of April. (As always on Aphidtrek, click on the photos to enlarge.) Just to put this place into perspective, Lake County is one small piece of eastern Oregon.

This is the view from camp toward evening. In the distance is Hart Mountain. Probably fewer than 50 humans live between the camera and the mountains in the distance. The sagebrush steppe shown here is typical.

It is comprised of 21,432 square kilometers of land, in which about 8,000 humans live. That much land is about two thirds the size of Belgium (30,528 square kilometers). About 70% of Lake County is owned by the federal government and is open to the public for recreation.

This time of year we stay in the desert lowlands which are managed by our Bureau of Land Management. Later in the year we will climb into the mountains and camp on Forest Service lands amongst the pines and firs.

On this trip we drove about 100 km north of home on our major highway, then turned off into what we call dirt roads, into the hills and desert, to reach Juniper Mountain.

Another 15 km or so along roads of rock, dirt, and mud found us a campsite amongst the junipers and sagebrush with a view of thousands of hectares of uninhabited land.

This kind of trip requires a special kind of vehicle; for us, a Toyota pickup truck, and for me, a mountain bike for further exploration. No maintained campgrounds here, we make our own camp, dig a fire pit, and park the vehicle in the trees.

The inland parts of Oregon are mostly dry, near-desert sagebrush steppe. This campsite is dominated by two species of sagebrush, Artemisia tridentata and Artemisia arbuscula, the latter known as ‘low sage’ and former as ‘big sage.’ The elevation here is about 1600 meters, going up onto Juniper Mountain behind camp, which peaks at about 2,020 meters. This kind of habitat sees a long cold winter and a dry hot summer. The sagebrush steppe is interrupted in places like this by stands of juniper trees, which utilize certain soil/geological types that suite their need for abundant subsurface water.

The junipers grow in certain soil- and aspect microclimates. Our camp site is the shiny speck in the trees in the center of the photo (click on the photo to enlarge).

As is our way, the first trip of the year was an especially nice weather weekend, sunny, not very windy (mostly less that 15 kph), and warm for this time of year (near 0 C at night, about 17 C during the afternoon).

It feels like good aphid collecting conditions, but here, spring is just beginning. Only a few specialized herbs are in bloom, the grasses are just starting to grow, and the shrubs breaking buds. In another month, this landscape will be full of the colors of desert flowers, including Lupinus, Delphinium, Castelleia, Eriogonum, Crepis, and much more. But this weekend, it takes a little hunting to find most of these plants just pushing through the dry dusty soil surface.

Aphids are few this time of year, but easily detected. The fundatrices of Obtusicauda, Pleotrichophorus, and Pseudoepameibaphis hatched a couple weeks ago from their overwintering eggs on Artemisia and are about 10 days from maturing to adult and beginning the new aphid season in earnest. On the psyllid side, over-wintered nymphs of Craspedolepta are growing again on Artemisia and heading toward adulthood in a few weeks. I don’t collect my bugs this time of year, preferring to stick with collecting adults when they are ready, but a walk through the early spring landscape is just as interesting as any time– it helps put into perspective everything that is to come throughout the growing season for this place.

We seek out places like this to study nature, doing our natural history thing, but equally we come here to enjoy the quiet, isolation from human noise, and soak in some amazing wild lands of the west.