I spent a lot of 2021 away from Aphidtrek; it was a busy year, full of newness.

Pseudoepameibaphis

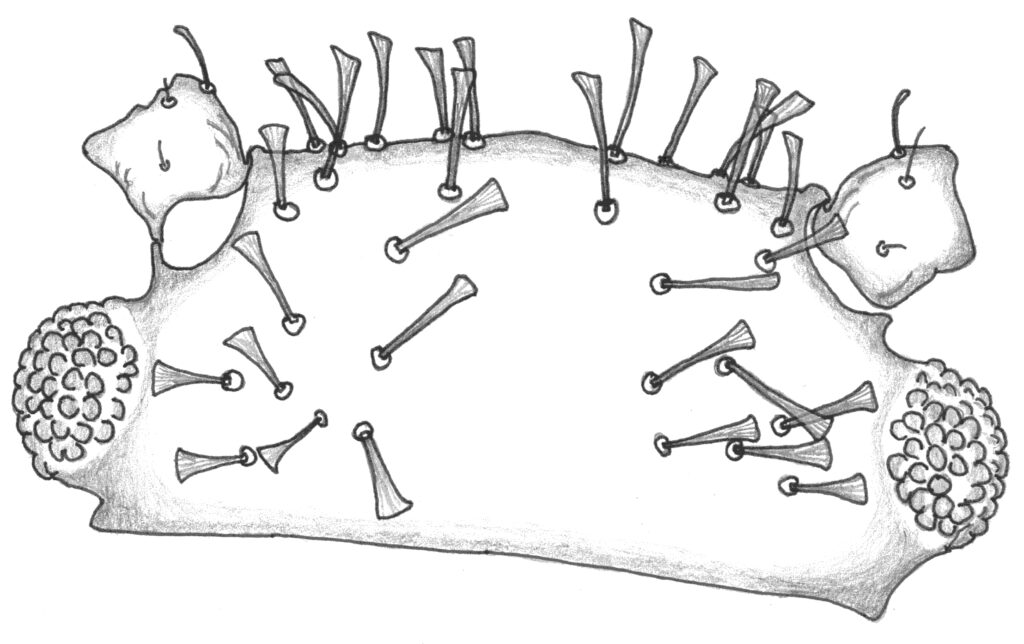

The first couple months of the year I spent diving into the taxonomy of Pseudoepameibaphis, one of my beloved genera of sagebrush aphids. This work followed years of intentional collecting of this genus everywhere I went, from roadside dog peeing stops to the tops of the highest mountains we hiked to. A decade of samples had finally set the stage for a thorough evaluation of what I had found and an attempt to align that with what was previously understood. I did much of the usual – sorting samples into what seemed like species (far more than we have published names), making measurements, thinking about host plant specificity and lack thereof, comparing to old literature, and so-on. I also drew. After 30 years of drawing my specimens the same way — camera lucida with pencil onto paper, tracing onto drafting film, touch-up and stippling with black ink – I switched to drawing directly onto paper starting with pencil and camera lucida, followed by black ink for outlines and shading with pencil to finish the look. It worked well and was much more enjoyable than stippling in black ink.

Roger Blackman, Macrosiphum

About the time that I was setting my Pseudoepameibaphis work aside, intending one more year of field research before preparing a publication, I was asked to submit a manuscript in honor of a colleague, Roger Blackman, marking his 80th birthday. Having shelved Pseudoepameibaphis for a year, I decided to quickly write up one of my undescribed Macrosiphum. But which one? I chose one that I’d made a lot of progress on while living in southern Oregon: a species with unusual tarsi, living on extremely sticky plants called Silene (a.k.a. catchfly). I had recently found several new sampling sites near Lakeview, had numerous specimens of a very similar species that I wanted to cover in conjunction with it, so I figured a paper was possible by the deadline in late spring. So, a quick shift in my aphid work to another new species!

Packing up, Moving out

In March, we got the news: our long-awaited opportunity to relocate to western Colorado had finally come. Moving for a new job (Gina’s), we immediately had to act: plan a trip to look for houses, put our house on the market, finish up our projects or put them into dormancy. I quickly decided to finish my new Macrosiphum paper before moving; it would take every spare moment while making plans for our relocation – a project we would undertake alone, from packing and cleaning to loading and driving. Everything came together. Just as I finished the manuscript and sent it to colleagues for peer review, we had to start the physical work of moving. Our soon-to-be new home would be a house with three irrigated acres in a warm desert valley. It will be our new place to connect with, to nurture, to plant shrubs and trees that we hope will far outlive us. Through this process of hard physical work most days for 2 months, I learned that my middle-aged joints and muscles could still accomplish much and benefit from the physical demands. After getting moved in, we learned that we could dig 57 post holes and build more than 100 meters of post-and-pole fence. It felt good to be done, and the dogs appreciate having their own clearly defined space.

Before moving, I transplanted plum and cherry seedlings from our greenhouse into a large pot. We moved these babies to Colorado. In October, these became the first row of trees planted on our new place, the first batch of many food-producing plants we’ll have here.

The Mother Ship of North American Aphidology

My aphid studies began in 1988, landing a summer job for Gary Reed, who gave me aphids, aphid traps, and a copy of Miriam Palmer’s “Aphids of the Rocky Mountain Region,” asking me to try identifying aphids we found in eastern Oregon. At the time, this book was by far the best resource we had in all of North America. So for me, the Rocky Mountain Region has been like the mother ship of aphids throughout all my research and exploration, everything I find being somehow tied back to what my aphidology ancestors (Gillette, Hottes, Knowlton, Smith, and especially Palmer) had found in Colorado and neighboring states. I had traveled through the region a number of times over the years and had a vague sense of it – what it must have been like to collect those samples from the 1880s onward. I imagined Gillette and Palmer on collecting trips, driving rickety cars on terrible roads, carrying multiple spare tires and tools for the frequent carburetor adjustments that would have been necessary as they rolled up and down the mountains. Now, our new place is among the sampling sites in Palmer’s book – just one example is the type locality of Macrosiphum yagasogae (=M. insularis): Mesa, Colorado, which is visible from our new garden.

Hypotheses

Almost daily walks in the deserts and forests near home lead me to make hypotheses about aphid biology; I suspect that aphids of deserts and seasonally dry shrub-steppe habitats may be different from aphids of forests and other damp places. For example, what’s the interaction of aphids and the local Artemisia bigelovii? Like other sagebrushes, this plant is extremely drought tolerant. However, it seems to be specially adapted to the common pattern of seasonal drought in the Southwest: dry much of the winter and spring, with monsoonal moisture in mid-summer. This contrasts with sagebrushes in the lowlands of the Northwest, where rain falls almost exclusively during winter and sagebrush must endure a summer drought. So, A. bigelovii is not well-prepared to support aphids in spring and early summer. Does it support aphids at all? My hypothesis is that yes, it does: in the fall and very early spring. And, this is what I observed in 2021: Obtusicauda and Epameibaphis widely colonizing A. bigelovii in September and October. You might wonder, then, where the aphids go during later spring and early summer. My hypothesis is that they migrate up in elevation to colonize sagebrushes that benefit from winter snowfall and enjoy a strong spring and summer growing season. These include mountain sage, Artemisia tridentata vaseyana, low sage, Artemisia arbuscula, and silver sage, Artemisia cana. I have similar hypotheses about other desert-inhabiting aphids in this part of the world. It will be fun doing the field research to accumulate evidence and examples.

Place

Connecting to the places I live has always been important. And by “place” I mean the biology and geology all around me, whether the spiders running through my garden plots, the Geocoris big-eyed bugs hunting through the grass like tigers of the insect world, to sweeping and complex ecosystems of canyon, desert, and forest. This place, western Colorado, is my Place now, where I plan to live and study the rest of my active life. Learning a place never ends, and that’s the joy of it. Starting big with learning the landscape, then learning the occupants of the landscape and its history, to uncovering layer after layer of complexity and interactions, thinking about forces that brought it here, and where it will go in the future. Curiosity cannot be extinguished, it just delves deeper into layers of complexity, noticing detail after detail. Each day brings a sense of anticipation – what new details will be noticed for the first time today?

The webs of a Place

When I think of a place and what it means to me, it feels like a web of micro-places inhabited by a web of beings. All of these are interacting. Not all possible interactions are happening all the time. An aphid can find a plant and live there for a time before moving on. An owl lives in a draw this winter, eating the local rodents, fertilizing its home trees with pellets and manure. Ravens gather to socialize among the boulders and junipers of a shallow canyon, bringing the sounds of their voices, the whooshing of their wings, and changing the behavior of all the vertebrates in the area. The elk gather for a time on a plateau among the canyons, leaving a layer of manure marbles. Junipers reach into the web, blooming in billowing clouds of pollen, later in puddles of waxy blue berries to be washed down the arroyos, eaten by coyotes. The webs connecting all the beings and micro-places are effectively infinite and pulling them up and peering into them is the lifelong process of getting to know and connecting to Place.

2021 was a lot of work, and we brought many life changes into it. Now, the Solstice has passed, the sun is returning, I feel a simmering hiss of life all around me, waiting to vibrantly boil over when spring comes.