Oh my, I’ve let the time slip by. I started working on my 2023 recap in early spring of 2024. Good intentions floated happily around for many weeks until finally inspiration and intentions waned completely. Now, with 2024 almost gone, I want to jot down some memories and events of the past two years, for myself as much as for anyone else. My memory of events almost 2 years ago is scant without reference to my photos and my aphids. So, a set of stories from those follows.

2023

This was my last full year of regular employment, having decided a few years previous to retire at the end of June 2024. So, I was working on the search for my replacement and preparing my work colleagues for my departure at the same time as I worked on building the next phase of my life: gardening, landscaping, connecting with land and nature, studying my aphids, and just generally enjoying my relative youth and remaining good health to their fullest.

I sowed many plants for the garden in March and April, carting them back and forth from greenhouse to garage. They grew during the day in the warmth of the greenhouse and were protected at night from frost in the garage. Eventually everything was planted in the garden. Hope reigned.

Then, in late June a river of cold air enveloped the garden and frosted tender plants to the ground. Peppers and tomatoes melted, potatoes sank to mere stems, squashes blackened. Studying the situation, it became clear that the unmowed, mostly wild pastureland that I had started converting to trees and flowers had somehow generated this cold air. In that field numerous baby trees were also killed, and even the toughest invasive weeds like prickly lettuce and lambsquarters were reduced to slime. No other yards in the neighborhood were frosted. Something was seriously amiss. So, the next day I studied temperatures at sunrise. My weather station mounted at about 10 feet (3 meters) above the ground measured temperatures around 43 degrees F (6 C). In cleared areas in the field, such as tree circles, the temperatures at ground level were about 23 F (-5 C), while temperatures at ground level in the driveway and lawn north of the house were about 40 F. Somehow the tall grass with small openings in it was creating a frost machine of epic proportions, a habitat only these tough grasses could survive. And, the cold air that it generated then flowed outward, killing everything that was remotely frost sensitive. It seemed my only option was to mow the field, removing opportunity for pockets of deep, still, cold air, to build up that had frosted and killed my plants. I had thought I might have to mow the field eventually to manage the straw accumulation, or to manage weed population shifts, or to improve the appearance. Never had I imagined that frost would be the cause. So began a multi-year effort to mow 2 acres of former pasture to limit freezing damage to my garden and baby trees.

The garden recovered remarkably well and produced huge volumes of food. By October the freezer, curing table, storage boxes, and cupboards were full.

Along the way we had a handful of good outings to camp, hike and sit in quiet deserts and forests, and look for aphids. One of the first camps of the year was on the edge of Roubideau Canyon in May. It was a weekend of beautiful views, if marked by few exciting aphids.

Later in the year we made a camping trip to some local mountains, including a long hike up a valley to alpine meadows and avalanche chutes.

In the fall we made our annual trip to New Mexico. The destination was far south near Carlsbad. While the aphid collecting was mostly very difficult we did find success in collecting many more good specimens of an unusual Wahlgreniella aphid on a mysterious rose at Sunspot in the Lincoln National Forest. The trip provided good camping along the way, and time to reflect on the beauty of nature.

We had many notable visitors to our gardens and field during 2023. The winter is always the time of raptors – numerous hawks, falcons, owls, and eagles flying past every day.

Throughout winter and spring foxes frequent our land to hunt voles and mice. My handy trail cam captured some nice photos of our canine friends.

During the summer we had an unusual amphibian visitor – a mature bullfrog somehow wandered across the landscape to find our temporary pond.

In December another amphibious visitor: a tiger salamander was found overwintering in the compost. It was safely relocated to live out the winter under a pile of straw mulch.

Perhaps the most remarkable visit I documented was on December 24th. A cougar (a.k.a. puma, mountain lion) walked along the trail I maintain in the grass along the southern edge of our field. What a treat! While this animal is arguably dangerous, I am overjoyed with visits like this. Yes, the cat may be dangerous, but I’d far rather die of a snapped neck under the teeth and claws of a cougar than at the hands of the corrupt, profit-driven U.S. ‘health care’ industry.

Throughout the year we are blessed with amazing sunsets and sunrises. Daily reminders to stop and contemplate life and beauty.

2024

January of 2024 brought my last trip to central Washington State for the Washington-Oregon Potato Conference, a key landmark of each year of my working life, my ‘career.’ At that event I was honored by the Washington potato industry with a special award at their annual dinner event (https://youtu.be/K3GRJtoHop4?si=yb4Z8bAVgBSiu_5b). It was humbling and was made extra special by the attendance of my sons and nearly life-long friends and colleagues.

Early in 2024 our 8-year-old little brown dog Mina turned up lame, the diagnosis eventually being torn cruciate ligaments in both knees and severe arthritis already present in one. She was reduced to walking on leash and no more than about 10 minutes per day, this reduction from her extremely active, long-hiking, rock-climbing self. Some weeks of despair and sadness ensued, but eventually we found a dog physical therapist who, over the past 8 months, has helped us help Mina back to nearly full mobility. We hope she can enjoy the next few years living as actively as she wants to. We’ll see.

Late winter was again garden prep season. I sowed fewer things in pots and the greenhouse than usual, but there was still plenty. The weather was milder than 2023, requiring less carting my seedlings back forth from greenhouse to garage. One new addition this year was semi-formal cone-pit biochar production. Converting our shrub and tree trimmings and other woody debris into biochar, a wonderful soil supplement, was interesting and enjoyable. The incredibly lush garden growth during mid-summer suggested that the biochar was a benefit! 2024 was the second Year of the Flower in our gardens, with numerous annual and perennial flowers in the vegetable patches, the tree circles, and the ornamental border around the house. Flowers rock.

As usual, we had a spring camping outing in April, this time to Disappointment Valley a couple hours’ drive south-southwest of here. Alas, it was a bit disappointing in terms of aphids, but it did not shirk on providing good landscape views.

One of our first mountain camps of the year was in June to the edge of spring on Black Mesa east of home. Here I also struggled to find aphids due to the early season, but as usual I was able to find a few while enjoying the solitude of a dead-end road near the banks of snow farther up the hill.

The end of June was the end of my ‘career’ in potato research administration and paper shuffling. Gina asked me what I wanted, and I said an opera cake. She was a gem and spent a day making one for me! It was then on to the serious work of building the landscape I hope for on our property, getting stronger and wiry myself along the way. This included the beginnings of my intention to be more creative in my old age.

2024 was the Year of the Toad on our property, with numerous toads hiding in a hole all winter, followed by a strong breeding pair producing eggs in our seasonal pond. The swarm of tadpoles was too many for our little pond, but quite a few nonetheless matured to the point of hopping away into the garden. There, the larger toads seem to help very much with my squash bug and pill bug plagues.

Our best collecting trip of the year was to southern Idaho and back. Southern Idaho to see my brother and hang out with a fellow insect collecting naturalist geek. Along the way was a camp on the slopes of Mount Timpanogos near Salt Lake City, Utah. There, the aphids were everywhere, on every plant that can host aphids. It was a bonanza of collecting. It was also the first time a moose has walked through our camp!

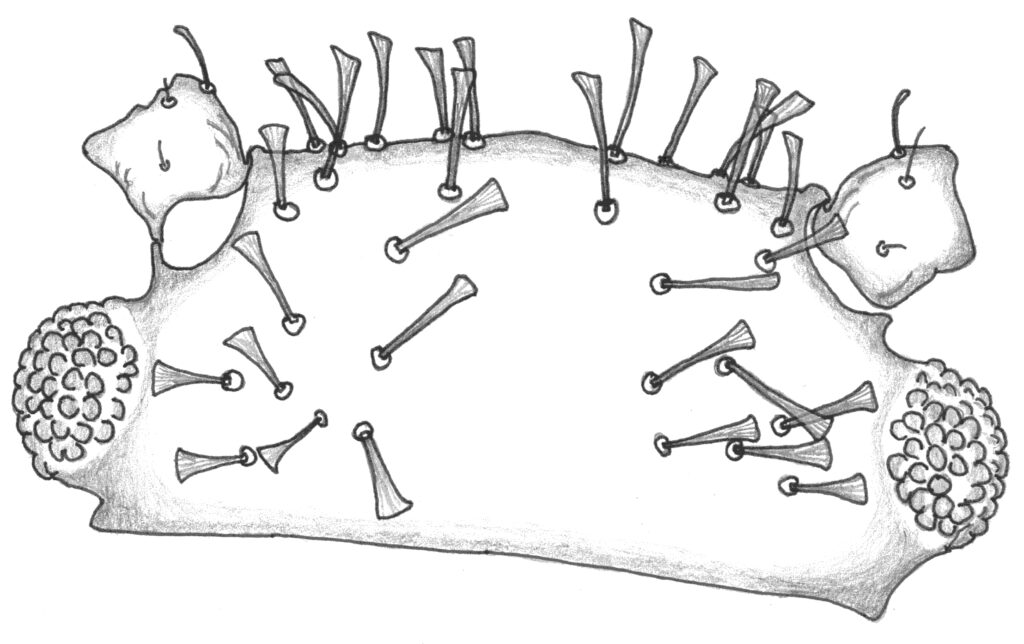

One of my final collecting outings was a walk up Roubideau Canyon from the bottom. Here I found three species of Capitophorus living on our native Elaeagnaceae, Shepherdia argentea. These included what appeared to be the primary host form of a putative new species that spends the summer on poverty weed, Iva axillaris.

Fall brought some unusually early snow followed by a December with zero precipitation – a reminder that we live in the desert. And of course, fall brings the best season for sunsets.