[Remember, to see full size versions of the photos, just click on them!]

I try to be cheerful about my aphid research and field work. I really do. Sometimes, however, a person has to speak out about injustice and exploitation. Since my special interest in life is the natural environment around us, I herewith speak out about injustice wrought by our federal government on land owned by we the people. Folks who live in or frequent the forests, sagebrush steppe, and grasslands of the western U.S.A. will know something about the ways in which public lands are exploited by private companies at little to no cost. However, many U.S. residents and others around the world will have no idea what I’m writing about below.

As a natural historian in the western U.S.A., a major challenge in my work is finding examples of plant communities and ecosystems that have not been severely damaged by one of three things: mining, logging, and livestock grazing. I’ll cover the latter in this post.

The history, extent, ecology, and politics of grazing on public lands in the U.S.A. is a book-length subject. In fact, many books have been written on the subject during the past several decades (a quick internet search will show them to you).  There are also many interesting and/or aggravating videos on YouTube. Have a look.

There are also many interesting and/or aggravating videos on YouTube. Have a look.

A very nice primer on the subject was published by The Center for Biological Diversity. One of the key points made in their report (which you can see by clicking on the image) is that it costs the federal government far more to support grazing than it receives in payments from ranching companies. In other words, grazing on public lands is a subsidy to the meat industry.

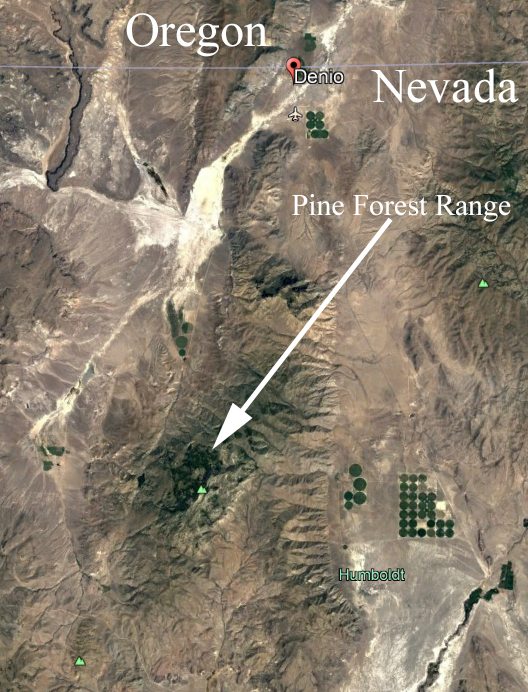

I cannot begin to cover here all the aspects of this issue that interest me. For this rant, therefore, I will highlight my feelings and observations from one recent trip we did to the Pine Forest Range of Humboldt County, Nevada.

Why is the Pine Forest Range interesting to an aphid biologist?

The Pine Forest Range is mostly federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, which is a branch of the Department of the Interior. The name is a misnomer of epic proportions because the mountain range is in an otherwise desert environment and has actual forest only at the highest elevations and on steep slopes with seasonal water or snowpack. The lower slopes of the range are at about 5,000 feet (1,524 meters) elevation, while the high peaks range from about 7,000 feet (2,134 meters) to the highest, Duffer Peak at 9,400 feet (2,865 meters). The land one might consider forest is varied, with highest peaks clothed in mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius) in some areas, and whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) in others. Some of the lower steep-slope forest patches are a mixture of trees, including whitebark pine, two or three willows (Salix spp.), and aspen (Populus tremuloides). The unforested ground is composed of various kinds of shrub-dominated systems, meadows, marshes, and grasslands. Ecologically, places like this are very interesting to me because the plant diversity from bottom to top of the mountains is great, ecological zones varied, and aphid diversity fascinating. In a single mountain range like this I can find aphids of wetlands, forest, desert, alpine habitats, and specialized habitats such as scree slopes, boulder fields, and mountain-top rock outcrops. This contrasts with more uniform habitats such as the moist forest slopes of the Cascade Mountains or the Coast Range of Oregon wherein the forest communities are much more dominant and uniform. One of my dream aphid research projects is to document all species present in a small but diverse site such as the Pine Forest Range.

The Pine Forest Range is also interesting because of the many springs that erupt from mountain sides and create year-round streams of clear fresh water. This contrast of year-round water in an otherwise desert-like environment can make for fantastic diversity. In a healthy riparian situation the stream will be surrounded by trees and shrubs, with a dense understory of herbs. There will be a steep gradient in habitat from stream edge with shade- and moisture-loving plants, through a narrow shoreline forest with plants that are adapted to moderately dry conditions, to the sagebrush and other plants of dry high-elevation desert. Along with this gradient in plant community, there is a gradient in aphids. I might find a species of Hyperomyzus (Neonasonovia) on Ribes deep in the shade and overhanging the stream, and it would be the same species as I find in a wet dense forest of western Oregon or the Cascade Mountains. As few as 10 or 20 meters away from this H. (Neonasonovia) will be Obtusicauda on the sagebrush (Artemisia spp.) or maybe Aphis (Bursaphis) on the Epilobium paniculatum.

On a personal and spiritual level, places like the Pine Forest Range offer the promise of immersion in a quiet, remote, natural setting that appeals to our primordial bonds to mixed landscapes of trees and plains (see “Biophilia” by E.O. Wilson).

The reality of the Pine Forest Range is almost unrelated to its promise.

Our camp site is in one of the most interesting parts of the range, with several springs erupting from the hillside, patches of aspen, seasonal wetlands, and it is within an easy walk of a large patch of mixed forest on a steep slope.

Some of the springs have associated wetlands, others erupt from rocky substrates and immediately form small streams. The result is a complex network of wet and dry ground, springs and streams, all leading down slope to the eventual creek that drains that portion of the mountains. All these habitat types, however, are severely damaged by cattle. The springs and ensuing streams are almost completely without riparian vegetation, the channels are down-cut with limited meander leading to drainage and drying of nearby former wetland. All these streams are large enough to be fish-bearing, but no fish are evident. Similarly, the landscape is essentially without amphibians that would otherwise live there.

The bogs and wetlands of the springs are severely grazed and trampled by cows. The open meadows are grazed and trampled to an extremely short stubble height. From the road, the aspen stands and sagebrush land look inviting, but closer examination on foot reveals that almost no herbs or grasses are left between the trees and shrubs, and that large swaths of the sagebrush have been severely trampled, leaving most plants in tatters scattered across the ground. The visible hillslopes, far up toward the highest peaks, are badly marred by on-contour trails, with cows traversing the steepest slopes and gathering in the wetlands as far as we could see.

The remains of a wetland fed by a nearby spring. The deep cow footprints in the mud are called “pugs.”

During our day-hike to investigate the area, we explored a dense forest slope south of camp. Once again, although it looked inviting and fascinating from a distance, upon entering the forest we found that the understory had been almost completely trampled and grazed by cattle, resulting in a depauperate community and a soil surface that was churned to powder.

Several species of plants exist in this area only nestled within the protective stems of willow thickets like these.

As for aphid collecting, many of the plants I was interested in were present, but most had been grazed and trampled to such an extent that the only evidence of their presence was tiny basal leaves or dry stalks that had somehow dodged the cows. Other species were present but had been driven back to protected sites among the stems of the willow thickets.

Bottom line is that this area is NOT a natural place. It is a ranch and it is managed for the purpose of raising cattle. While on paper these public lands are meant for multiple uses by the public, only one use dominates: grazing. Other uses, such as communing with nature and our spiritual self, studying natural history, and even hunting and fishing, are severely limited by the cows and their impacts.

Our camping area: beautiful landscape in the background, camping area in the middle, and destroyed habitat in the foreground. Aphids don’t stand a chance here.

Additional thoughts

As I walked through the landscape near our camp in the Pine Forest Range one thing that came to mind is how the local Native Americans might feel. Before colonization surely the area where we camped was a fabulously useful site for fishing, hunting, and gathering. It was likely considered sacred. How might a person transported through time from year 1500 feel, standing at the site of our camp and witnessing the destruction of such a place?

Public land grazing represents a public subsidy of the meat industry. Meat, milk, and egg production as a category is one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. As noted in a recent article in The Guardian, “Raising livestock for meat, eggs and milk generates 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, the second highest source of emissions and greater than all transportation combined. It also uses about 70% of agricultural land, and is one of the leading causes of deforestation, biodiversity loss, and water pollution.” Our public funds that support grazing subsidize meat production (contributing to low meat prices and encouraging meat consumption), support all the inhuman cruelty that comes with large-scale meat production, and directly contribute to climate change. Is this how we want our public lands and public funds used?