Capitophorus van der Goot

This page updated: December 2024.

For several years I’ve been pursuing better understanding of the native North American Capitophorus and also aiming to build out my representation of the adventive species living here. This effort was actually sparked by my first collection of Capitophorus on Ambrosia way back in 1993, the Ambrosia growing as a weed on the streets of Kennewick, Washington. These specimens ran to either C. jopepperi or C. shepherdiae in the key by Corpus-Raros and Cook (1974), but did not seem to match either very well. Since then I have spent time most autumns looking at the fall migrants of Capitophorus on Elaeagnaceae wherever I’ve lived or traveled, trying to find members of our native species in the ocean of non-native C. elaeagni and C. hippophaes. Then, in June of 2017 I found in southern Oregon a strange, small Capitophorus on roadside specimens of the common native weed Iva axillaris (Asteraceae; poverty weed). It is similar in general shape and morphology to the thing I call C. shepherdiae (see below) when collected on Ambrosia, but it has some key differences as well. Collecting Capitophorus on Ambrosia and Iva axillaris has continued since 2017, hoping that a diversity of specimens, plus gathering the rarely seen alate viviparae, would shed light on the species-level separation (or lack thereof) between these taxa.

Along the way, I had been collecting C. essigi at high elevations from its summer host, Aconogonon phytolaccaefolium, and guessing that it may host alternate between this plant and Shepherdia at lower elevations. This heteroecy seems certain at this point based on my collections (see below).

Since moving to Colorado in May of 2021 I had a major advancement in my plant taxonomy knowledge that led to new and interesting samples and prompted a quick study of the native Capitophorus with clavate siphunculi in western North America. What was this plant identification epiphany? It was two-fold: first, I learned that separation of Elaeagnus and Shepherdia is very easy based on whether stem leaves are alternate (Elaeagnus) or opposite (Shepherdia); second, I learned that separation of our two native species of Shepherdia was also incredibly easy: S. canadensis grows in cool mixed forests, has speckly broad leaves, and a low and broad growth habit, while C. argentea foliage looks almost exactly like Elaeagnus (except it has opposite leaves), with long pale leaves, and grows in desert canyons and drainages far from the habitats of S. canadensis. Previously, I had not studied the distinctions among these plants enough to realize how simple the taxonomy actually was, and had therefore missed the opportunity to better understand all their Capitophorus species. This oversight in plant taxonomy had nothing to do with the level of difficulty, but just my lack of adequate study! It teaches me yet again to try harder on my botanizing.

Armed with this new knowledge and some very fun samples from fall of 2021, I spent some time in December curating and sorting my samples of Capitophorus. The results are reflected below and in my slide collection database released in 2022.

Species covered below (click on the name to jump to that species):

- Capitophorus elaeagni (del Guercio)

- Capitophorus essigi Hille Ris Lambers

- Capitophorus gynoxanthus Hille Ris Lambers

- Capitophorus hippophaes (Walker)

- Capitophorus shepherdiae Gillette & Bragg

- Capitophorus sp. living on Iva axillaris

- Capitophorus sp. living on Shepherdia canadensis

- Capitophorus xanthii (Oestlund)

Capitophorus elaeagni (del Guercio)

This aphid is widespread in North America, and especially common everywhere I have lived in recent years due to the ubiquity of its primary host, Elaeagnus angustifolia (a.k.a. Russian olive), which is common in the arid interior west, growing along natural and artificial waterways. Consequently, I have many photos and specimens, the hope usually being that the specimens will turn out to be something less common that will shed light on the questions I have about Capitophorus taxonomy (see above). Inevitably, almost all collections turn out to be the easily recognized C. elaeagni. This species migrates to thistles and related plants and is very common on various Cirsium species including Cirsium arvense (Canada thistle). It also happily uses other Elaeagnaceae as primary host including Shepherdia and Hippophae.

In December of 2021 I looked through all my samples identified as C. elaeagni just to confirm that I had not missed any specimens of other thistle-feeding species that might have made their way to North America. Alas, all were quite typical C. elaeagni. The only interesting variation I saw was some fall alatae with almost entirely dark siphunculi and other darker-than-typical features.

This is one of the species adventive in North America that penetrates deep into our natural systems. I find it in diverse forest types, open fields and deserts, from sea level to subalpine.

Capitophorus essigi Hille Ris Lambers

I first found this aphid in the mountains of northern Idaho together with Aphthargelia rumbleboredomia on its summer host, Aconogonon phytolaccaefolium. Among Capitophorus with clavate siphunculi in western North America, it is easily recognized by its short thin dorsal setae.

During study of Aphthargelia, I regularly saw C. essigi and it became clear that it almost certainly did not overwinter on Aconogonon. I therefore started searching the most likely winter host in the mountains that C. essigi lives: Shepherdia canadensis. A series of samples from Idaho and Oregon during fall of 2013 were clearly C. essigi. These included alate viviparae, alate males, and oviparae. I have since also found this species on S. canadensis in northern Idaho in 2014.

Capitophorus gynoxanthus Hille Ris Lambers

In curating my undetermined Capitophorus, I found a single alate vivipara collected as a casual on sedges in a swamp in Clearwater County, Idaho. With a combination of double spinal setae and cyclindrical siphuncili, I knew immediately this was not C. elaeagni. Based on much poring over keys and other information, it seems this specimen represents C. gynoxanthus (formerly considered part of C. horni in older literature). What this specimen was doing in a high elevation swamp is another thing altogether. Anyway, I now have a single alate determined as C. gynoxanthus.

Capitophorus hippophaes (Walker)

This is the other very common Capitophorus species in my area that is introduced from the Palearctic.

It overwinters as eggs in most areas I’ve collected it, on Elaeagnus angustifolia (a.k.a. Russian olive). This tree grows as a weed in wet places in otherwise desert environments. In wetter and warmer habitats, such as west of the Cascade Mountains, this aphid probably overwinters as viviparae on it summer hosts, Polygonum and Persicaria. This species was among the first I collected and tried to identify, way back in the 1980s. In those days I collected it very frequently in yellow pan traps meant to catch potato pest species such as green peach aphid, Myzus persicae. It was obvious to me that C. hippophaes was not M. persicae, but it took me a couple years to arrive at the correct species identification. Of course this all occurred before Blackman and Eastop’s pivotal work on aphids of the world, and in the time when my only aphid identification resources were Aphids of the Rocky Mountain Region by M.A. Palmer (1952) and Aphids of Illinois by Hottes and Frison (1931). They were actual books made out of paper.

Capitophorus shepherdiae Gillette & Bragg

Corpuz-Raros and Cook (1974) considered all specimens with clavate siphunculi on Ambrosia and Shepherdia argentea to be C. shepherdia. Their decision was based on morphology only – they had no good biological connections or host transfers to go on. Since then, it seems Blackman and Eastop were skeptical of this host alternation since they only mention, “Apparently persisting on this host throughout the summer, but morphologically similar aphids have been found on Ambrosia spp. in California and Washington, so there may be a partial migration which needs to be confirmed by transference tests.”

Based on morphology, I completely agree that the species found on Ambrosia out west is C. shepherdiae, and samples collected from S. argentea in Colorado during 2021 strongly support the idea of heteroecy. I have a sample from Elaeagnus, which indicates that genus may be acceptable in a pinch. Key is that hosts for this species seem not to include Shepherdia canadensis. I have samples of a similar species from S. canadensis in Oregon, Idaho, and Colorado; see below for some discussion of those samples.

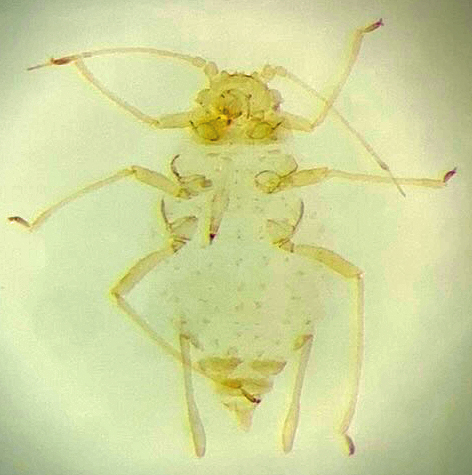

Capitophorus sp. living on Iva axillaris

As mentioned at the top of this page, I’ve been pursuing a possibly new species on Iva axillaris since 2017. This aphid looks much like what I am calling C. shepherdiae on Ambrosia. I have specimens collected on Iva from Oregon, California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming. Based on evaluation of all my samples and comparison to C. sheperdiae from Ambrosia, there are obvious features to separate the apterae, such as degree of rugosity of the dorsal integument, dorsal setae number and distribution, and color of the 6th antennal segment. However, I can find no clear way of separating the alate viviparae and alate males of these two ‘species.’ If I ever get around to working up a publication, something may emerge during the measuring and drawing process to separate the winged forms of these species.

For now, I am aiming to gather fundatrices and second generation apterae from S. argentea from near our new home during spring. It will be fascinating to see if they develop on the same S. argentea plants and whether the two species can be separated on that plant. Efforts in 2022-24 were unproductive. I have done two small host transfer experiments in the fall, one from Iva to Elaeagnus angustifolia, and one from Iva to Shepherdia argentea. Both were successful, with transferred viviparae able to develop to adult and produce offspring. I have not been able to follow such transfers through the winter. For the sake of thoroughness I may also attempt some host transfers someday between Iva and Ambrosia. Much to my satisfaction, I was able to collect numerous specimens (apterous and alate viviparae, oviparae, and alate males) of what I think is this species from S. argentea in our local Roubideau Canyon in October of 2024.

Capitophorus sp. living on Shepherdia canadensis

Up until December of 2021 I thought the species I get on S. canadensis, in addition to C. essigi (see above) was C. shepherdiae. Then, I was reminded of the species called C. hudsonicus described by A.G. Robinson from northern Manitoba near Churchill. Although his samples had been collected from mixed shrubs, he was confident that their true host was S. canadensis, which is known to grow at that site. So, once I realized the important ecological distinction between S. argentea and S. canadensis, I figured that my samples from S. canadensis may be C. hudsonicus. I figured it was not crazy to think that a single aphid species could live on S. canadensis from far northern Canada south in the mountains of the U.S. Feeling hopeful, I printed the description of C. hudsonicus and began comparing to my specimens. Alas, my samples seem almost certainly to be something other than C. hudsonicus. My specimens have ultimate rostral segment far too long and robust compared to Robinson’s; also, the sensoria on the antennae of alatae are small and scattered around the circumference of ANT III and IV, with a few also on ANT V.

This species seems to be monoecious on S. canadensis, living especially on plants growing in cool shady sites. I have samples of fundatrices in late May and apterous and alate viviparae and oviparae in late August and early September. My material is from Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and Colorado.

Capitophorus xanthii (Oestlund)

After years of tapping on Xanthium everywhere I see it, I finally found a good population of C. xanthii during 2021 and, as luck would have it, just a few hundred meters from our new house! Now, I am hopeful to find spring populations on Elaeagnus and to get decent photos. Wish me luck!