Devils Garden, Fremont-Winema National Forest

6-8 May 2016

We desperately wanted to get out this weekend, and in the face of a harsh weather forecast for thunderstorms near home in Lakeview but dryer to the west, we cast about for a place to try that A. would not be snowed in, and B. was interesting and would probably not be washed away during a thunderstorm. Looking at the map west of home, I found the words Devils Garden in a little sliver of national forest land north of Dairy, Oregon (Klamath County). On Google Earth, it showed as a round eruptive center from past volcanic activity, and it appeared there were some dirt roads right to edge of the rocky outcrop, which is about 1 kilometer in diameter. So, off we drove on Friday, once we cleared our day of conference calls, shopping, and tending the greenhouse.

About 2 pm we arrived at the edge of Devils Garden, and saw that we had made a good choice, assuming the storms didn’t make it that far west.

The volcanic tuff is a mixture of rock types cemented together that then fall apart to form all sorts of bizarre formations. Gina and Bumble in one of them.

The circular feature of ash flow tuff was clearly visible from the highway, and we just had to find a way down to it and select a camp site. Much rolling down sandy and muddy roads later, we emerged on the edge of Devils Garden.

Unsure about a camp spot, we got out to walk around. It’s an amazing gem in southern Oregon, with unusual plants amongst very cool rocks and formations. We walked for quite a while, exploring the formations and biology. Wasn’t long before I was hopelessly “turned around” and lost. Fortunately we had a cell signal and we both had our phones. We texted back and forth to locate each other and head back to the truck. Even Gina, my human compass, had a hard time walking back to the truck, and we both learned something about “walking in a circle” when lost.

Our camp spot chosen (with wild onions all around) we set up, cooked fajitas, and had a campfire all evening. Next morning I set off to look for aphids, which was a challenge. There were many promising plants and habitats, but few aphids found. Along the forest edge were many large and healthy patches of Geum triflorum, on which feeds an un-described species of Macrosiphum, but many plants inspected turned up no aphids. In one rock outcrop in the forest I found a site with 3

species of Prunus: P. emarginata, P. subcordata, and P. virginiana. Much hunting, but no aphids on any of them. There were at least 3 species of Ribes in the area, and I did manage to find some Nasonovia (Kakimia) and Aphis (Bursaphis), but they were scarce. Two species of sagebrush scatter the area, but even they were very lightly populated with Pseudoepameibaphis. Purshia tridentata was everywhere, from dense forest to rock outcrops and open gravelly slopes, but only a couple aphids and psyllids were found. I managed to find one Braggia fundatrix on one of a few species of shrubby Eriogonum, a couple late-instar nymphs of Macrosiphum on a fern (which I was able rear to adult at home), and some fundatrices of Acyrthosiphon macrosiphum on Amelanchier utahensis on the edge of the forest. There is a drainage on the southeast side that is a dense aspen grove filled with Smilacina and Vicia in the undergrowth (no aphids, though!).

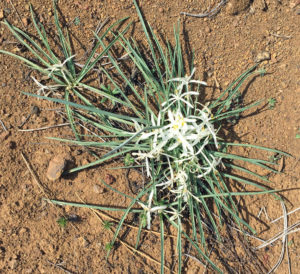

The final highlight was sitting back at camp reading up on the various unfamiliar plants seen during the day. One was Leucocrinum montanum, a lily that was the first known host of an aphid I have studied extensively, Abstrusomyzus leucocrini.

I had never seen the plant before except in photos. Unfortunately, much searching both above and below ground turned up no aphids. Along the way of reading and resting at camp, we were visited by a solo pronghorn. It walk along the nearby dirt road, stopped to watch me, then when Gina moved in the bushes (she was studying the soil, her wont), the pronghorn bolted out of sight.

The whole site is probably affected by the severe drought the region has faced over the past couple years. The wet winter and spring make the plants look good, but the drought has left its mark on the aphids. In many places these plants would have ended their life cycle last fall far earlier than aphids are adapted to, causing a terrible crisis for the aphids. But, I expect that by mid-summer the aphids will likely recover from their current population bottleneck, and may be extremely abundant in the fall.

By Sunday morning, no rain had come, the weather had been mostly mild and not very windy, and we headed home fully satisfied with a weekend away from home.